plate 1. Yellow pine needles frame a darkening Ozark sky.

Ozark Glades

by Joshua Heston

At first glance, the Ozark highlands appear remarkably plain, flaunting environments decidedly similar to those found in the Midwest and elsewhere.

Many nature books, when describing North American ecosystems, skip over the Ozark Mountains entirely, simply listing categories like oak-hickory forest, southern pine forest, cactus desert, tall grass prairie, cypress swamp or southern Appalachian forest (North American Wildlife, 19-20).

plate 2. Cactus in the Ozarks! Prickly Pear (Opuntia sp.) abounds in the rocky hillside glades throughout the Missouri Ozarks.

plate 3.An arid cedar glade ecosystem in the Busiek State Forest, Christian County, Missouri.

The Ozarks defy categorization because our highland mountain region include all of those habitats— sometimes within a few feet of one another!

Hillsides of yellow pine oft give way to thick oak-hickory stands. In the northwest regions of the Ozarks (up near Knob Noster or Harry S Truman’s birthplace of Lamar) tall grass prairie subtly unites with hills and hollers of the mountainous region. The southern reaches of the Ouachitas reach to Texarkana and its languid cypress stands.

No, often-times the Ozarks are unique not for a singular quality, but for the dizzying combination of qualities not typically found together.

Nowhere is this more evident than in a glade.

At its most simple definition, “glade” means an open space in a forest. Here in the Ozarks, it is just a little more complicated. Realize that our mountains — vastly older than magnificent Rocky Mountain peaks or craggy Appalachian ledges — were worn down by erosion numberless ages past.

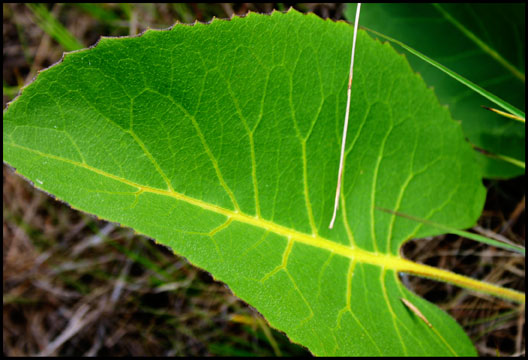

plate 4.Brilliant prairie dock (Silphium terebinthinaceum) leaves in a glade near Table Rock Mountain just off Highway 165, Taney County, Missouri.

plate 5.Beautiful Missouri primrose (Oenothera speciosa) abound in some open areas. The species is a succulent, thriving in dry, rocky soils.

Hence, when traveling into the Ozarks from the north, you do not drive up into the mountains but rather slowly down into an increasingly hilly landscape.

As this erosion took place, particular hillsides were washed clear of most any soil and — especially on south and westward facing slopes — Ozark glades formed. Soil scarcely clings to these rocky slopes so each rainfall perpetuates a specialized ecosystem.

Temperatures are higher here, the south-facing slopes absorbing hot, afternoon sunlight. Only certain plants can survive on the sparse soil. Only certain animals are attracted to this habitat.

Rough, knotty cedars (eastern red junipers) hug the rocks. Prairie dock, with wide, prehistoric-looking leaves sprout from beneath dark, volcanic-looking rocks. Showy Black-eyed Susans and coneflowers bloom in midsummer, lending a touch of the tall grass prairie.

But, most surprisingly, cactus (in the form of the prickly pear) can be found in abundance. Tarantulas roam over the rocks in the fall, copperheads occasionally slither from rock to rock. It is arid desert in the midst of green forest, both habitats serving as ancient signposts.

plate 6. Rock detail. The Ozarks are an ancient mountain plateau which has been slowly breaking down over the ages.

plate 7. Ominous and startling, tarantulas are common in the Ozarks. On closer inspection, these unique spiders are a beautiful and interesting part of these hills’ wildlife.

plate 8. Thin, reddish soil already shows signs of erosion. Glades are a self-perpetuating ecosystem, threatened only by non-native plant invasions (such as mimosa) or industrial development.

plate 5. A Black-eyed Susan (Rudbeckia hirta) glows in the warm afternoon sun.

These Ozarks were once a crossroads for ancient peoples: A path leading from the dark, moist hardwoods beyond the Great River (or Misi-zibi as the Algonquin peoples called the Mississippi River) to the harsh lands and complex cultures of the great American Southwest.

Along the way — at this tumbled crossroads called the Aux Arcs — glades pointed the way west, small patches of desert amidst a strange, almost holy, conglomeration of ecosystems.

Forever old, forever young. Consistently defying expectation and description. These old, old Ozarks.