Mushrooms

by Joshua Heston

Mushrooms (and toadstools) are strange critters. Sometimes edible (and delicious), sometimes hallucinogenic, sometimes fatal, they’re not plants at all but fungus — spore producing organisms that feed on organic matter.

They are incapable of photosynthesis. They eat dead things. Long-connected to folklore, wildcraft and European poetry, the lowly mushroom and toadstool deserve respect. Hard to find, hard to identify, springtime mushroom hunting is best done with an experienced guide.

Morel mushroom hunting takes on a life of its own across the Ozark Mountains — and throughout the rural Midwest, for that matter. By late April here in the hills, folks begin searching far and wide, across hill and valley (and often in very particular secret spots) for a cache of wild mushrooms just ripe for picking and frying. Indeed, it is a source of pride for many — number of mushrooms found, weight of the haul, so on and so forth.

More than a few of my family go mushroom hunting on a regular springtime basis. And, while a good morel, sliced open, dredged in egg and flour and fried up crispy is hard to beat, it has long been my least favorite of wild hunting.

For one, they can be devilishly hard to find. With a mild and dappled aged-leaf-and-wood color and pattern, mushrooms hide with the skill of a gun-shy turkey on high alert. I’ve suspected them of actually getting up on their little tendrils and sneaking off when my back is turned.

Second, the appearance of morels is brought on by climbing springtime temperatures and a high degree of moisture — a combination equally favorable for ticks and copperheads.

Lastly, just because a huge patch of morels appeared last year under that big elm right next to the creek and five paces up from the rock outcropping doesn’t mean they’ll show up there this year.

A mushroom is literally the “fruiting body” of a fungal growth — sounds disturbing, doesn’t it? — and those spread-by-the-wind fungal spores’ sprouting habits are nearly impossible to predict.

Some folks are just plain lucky — or far more skilled at mushroom-finding than me (my father and sister are two of them). No, give me mulberry season instead. Mulberries have the decency to re-appear right where we left them last year with so little guesswork, plus they make a good cobbler.

However, if you’ve a chance to sit down to a plate of wild-caught morels, split, twice rinsed (the little black beetle critters need to get flushed out first), dredged deeply in a bright egg wash, a flour-salt-and-pepper bath, and dropped into a cast iron skillet of shimmering hot grease, you’d best do so.

Even I’ve got to admit they’re mighty good.

May 9, 2013

The Elf & the Doormouse

- Under a toadstool crept a wee Elf,

- Out of the rain to shelter himself.

- Under the toadstool, sound asleep,

- Sat a big Doormouse all in a heap.

- Trembled the wee Elf, frightened, and yet

- Fearing to fly away lest he get wet.

- To the next shelter - maybe a mile!

- Sudden the wee Elf smiled a wee smile,

- Tugged till the toadstool toppled in two.

- Holding it over him, gaily he flew.

- Soon he was safe home, dry as could be.

- Soon woke the Doormouse - “Good gracious me!”

- “Where is my toadstool?” loud he lamented.

- -And that’s how umbrellas first were invented.

— Oliver Hereford

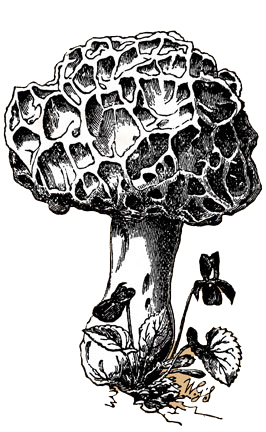

Plate 1. Yellow Morel, Morchella esculenta.

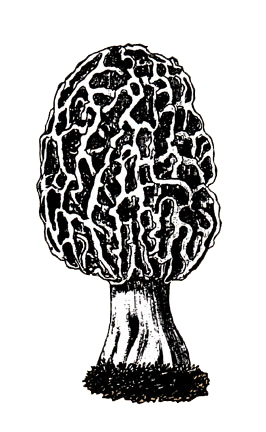

Plate 2. Black Morel, Morchella elata.

Plate 3. White Morel, Morchella deliciosa.

If you like this article, be sure to check out these!

- Fried Morel Mushrooms

- Eureka Springs: Southern Gothic

- Ozark Magic & Hoodoo

- Miss Shirley’s Fried Okra

Plate 4. Thick-footed Morel, Morchella crassipes.

Common Morel (Morchella esculenta)

Size: 1 to 2 inches wide; 1 1/2 to 4 inches tall. What to look for: cap continuous with stem, gray or light yellow to brown with rounded ridges and rounded or irregular pits; stem white. Habitat: old orchards; broad-leaved forests; grassy areas; low wet areas; near recently dead elm trees; occasionally in gardens.

— page 559, Wernett, Susan J., et al. North American Wildlife. The Reader's Digest Association, Inc., 1986.