Ozarks’ River Mussels

by Joshua Heston

A rickety white steamboat plies the waters of the White River, slowly chugging upstream to the tiny port town of Forsyth, Missouri. The pristine Ozark landscape glides past: untouched hardwood forests, towering stands of pine. Limestone bluffs, white in the slanting, golden afternoon sun. Beneath the shallow bottomed boat flows clear, cool river water, teeming with life.

A moment in time — the untamed White River of Missouri and Arkansas — before the impoundment of this tumultuous, defiant waterway. And despite the good-old-days nature with which we tend to remember days gone by, this was an era with little understanding of conservation.

As the 19th century gave way to the 20th, thousands of acres of grand old forest would be clear cut — the wood sold to feed a growing industrial hunger. Railroads were being established nationwide and railroads needed good lumber on a grand scale, as did the urban growth of St. Louis and Kansas City.

The Ozarks’ natural resources appeared endless. Folks truly believed nature could be harvested without consequence and nowhere was that more evident than in the gathering of freshwater mussels.

In the Victorian age of industrialization, common items became mass-produced for a worldwide market. Craftsmanship fell into decline, replaced by the mechanization of assembly line and power tool — even if those lines and tools were powered by pulleys, cables, and running water or rudimentary electrical grids.

Looking like so many small, sharp-edged rocks — slimy and dark — freshwater mussels’ pearl-like shells were perfect for the emerging button industry. And Ozarkers found a ready market in this resource. Shellers jury-rigged lines of heavy “crow-hooks” stretched across long bars which were then trolled through the clear, cold water behind john boats.

Mussel species snap shut when provoked and crow-hook trolling proved an efficient method of collection. The mussels would close on the hooks and be hoisted up. Onshore, buyers steamed the mussels and removed the innards (which were then sold as hog feed). The cleaned shells were taken by barge to local button factories.

Early records suggest as many as two million pounds — and an estimated eight million of these little critters — were pulled from the White River each year (Fresh-water Mussels and Mussel Industries, from the Bulletin of the Bureau of Fisheries Volume 36, 1917-18).

Even before you count in other damaging factors, it is clear the freshwater mussels of the Ozarks could not sustain this level of harvest.

Far more than slimy rocks, freshwater mussels are diverse, fascinating, complex — and beautiful. Of the approximately 69 species of native mussels, 14 are in danger of being completely destroyed throughout their range. For several, our common riverways are home to the very last populations on earth.

The common names are a peek into the nomenclature of the Ozark shellers’ language of a hundred years past:

Pink mucket, spectacle case, slipper shell, rock pocketbook, heel splitter, snuffbox, southern hickorynut, Ouachita kidney shell, deer toe, Ozark pig toe, maple leaf, pistol grip.

Beautiful and diverse, it is the life cycle of freshwater mussels that best illustrates the intricate and astonishing design of these animals.

You see, freshwater mussels of North America require a bit of assistance to produce baby mussels — more specifically they have to trick native fish species into lending a helping hand (though in this case it is a helping gill).

Mussels filter vast amounts of water in order to survive. In season, males release sperm, clouds of which float downstream where some is filtered by females of the same species. When those females sense they have filtered sperm — rather than food — their gill chambers fill with eggs and become fertilized). The result is tiny, developing larvae called glochidia.

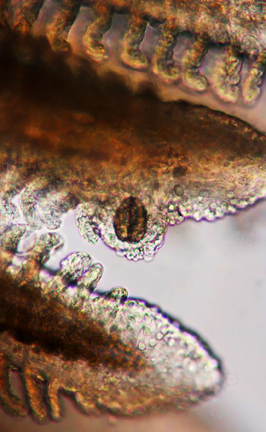

Now, you would think that’s complex enough but in the case of these mussel species, we’re just getting started. These glochidia have no internal organs but are grouped together into what is called a conglutinate. Think of it as an “egg sac” or a “nest” of sorts.

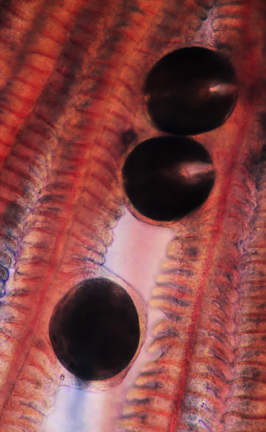

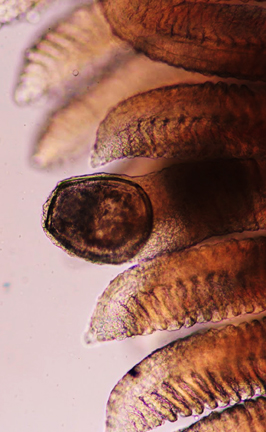

But now the conglutinate — filled with thousands of microscopic larvae — has to be delivered to a particular fish species in a particular way. Those tiny, organ-less larvae must land on certain fishes’ gills, where they are covered by the blood-rich tissue and begin to grow. If they get on the wrong fish? The glochida are sloughed off by the fish’s antibodies.

When successful, the glochidia remain in the fish’s gills — like tiny little seed ticks — developing quickly for a couple of weeks before dropping off where they grow into adult river mussels (if they happen to land in a suitable area of the riverbed). Amazingly, some species can live as long as a century.

But first that mother mussel has to trick a fish into cooperating before the life cyle can continue.

The tricks are ingenious: Minnow lures, crayfish lures, wet fly lures, catch-and-release, and self-sacrificing methods — all are options for various mussel species.

The Ouachita kidney shell (Ptychobranchus occidentalis) releases its “egg sac” disguised as a twitching pale grub — complete with “eyes.” When the tropical-looking orange-throat darter (Etheostoma spectabile) comes in for a closer look, the fish may mistake the “egg sac” for a real-life meal and pounce. As the darter breaks open the membrane, a cloud of glochidia is released into the fish’s mouth. Some glochida that aren’t swallowed are carried to the oxygen-rich gills.

Equally complex, the Arkansas brokenray females (Lampsilis reeveiana) have a mantle flap — a sort of flappy lip on either side of the mussel shell’s “open mouth.” Just inside is the conglutinate waiting for a fish host. The mantle flap twiches, looking like a minnow, complete with fins and eyes. The perfect decoy, the “minnow” lures predatory fish — like smallmouth bass (Micropterus) and goggle-eye (Ambloplites) — into striking. The glochida are then released in a cloud.

Perhaps the most comical strategy is that of the snuffbox mussel’s (Epioblasma triquetra), a species which uses the logperch (Percina caprodes) to continue its offspring’s life cycle. Highly curious, logperch are darters that scrounge the river bottom, turning over pebbles with their shovel-shaped noses. Blessed with a comparatively well-built snout, the darter accidentally sticks its long nose into the snuffbox, which clamps down and begins puffing clouds of glochida up the unsuspecting logperch’s snoot and through the gills.

The rainbow mussel (Villosa iris) needs a smallmouth bass host and consequently the female mussels produce a multi-colored and tentacled membrane which — when rippled — looks ever so much like a crawdad walking across the river bottom.

The endangered scale shell mussel (Leptodea leptodon) sacrifices itself by becoming all-too available to prey. When successful, the fish host — a freshwater drum (Aplodinotus grunniens) — chomps down on the mother, crushing her shell and killing her. The glochidia cloud is thus released into the attacking fish’s gills.

Complex. Ingenious. Beautiful. Each species’ methods are tailored precisely to attract the fish host needed. But complexity does not come without a price. The more complicated the mussel’s system, the more vulnerable it becomes.

Our industrious ways of taming the river — and surrounding landscape — play havoc on these little water filterers. A cement low-water bridge may block the requisite fish host from traveling upstream. As a result, that particular mussel population has only one generation before the stream becomes a dead zone.

Mussels filter out all sorts of bad things in the water column but anything that eats also has to poop. Without free-flowing water, mussel beds may produce enough ammonia to kill themselves, smothered in their own waste.

Deep water doesn’t flow quickly. The lake impoundments of Taneycomo, Table Rock, Beaver and Bull Shoals killed untold millions.

Too much fertilizer — even in the simple, natural form of manure — causes eutrophication: algae bloom that deprives the water of oxygen.

The big dams’ peaking cycles — convenient for selling electricity — artificially create 50-year floods and drouths repeatedly through the season. Consequently, lake water is either far too deep or far too shallow to support mussel beds.

Recently, the introduction of the invasive European zebra mussel (which does not require a fish host to continue its life cycle) puts further pressure on already threatened species. Zebra mussels reproduce faster and eat more, thus starving out native mussels.

The road to recovery is a slow one though the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service in conjunction with Missouri State University’s biology department works hard to counter population depredations.

“Freshwater mussels are like vacuum cleaners,” explains Bryan Simmons of the USFWS, “They remove nutrients from the water column and deliver nutrients to the food chain. Plants utilize the nutrients. Insects eat the plants. Fish eat the insects. Birds, snakes and mammals eat the fish.”

“Mussels clean the water column very efficiently. In one day, the average river mussel will filter eight to 10 gallons of water. Filtered water is a billion-dollar industry and mussels do it for free.”

Chris Barnhart, PhD, of the Missouri State University’s biology department and the Kansas City Zoo staff work together — along with Simmons — to propagate endangered mussels, returning tens of thousands to their native habitats.

Simmons also assists in creating new rules for publically funded projects (including Bagnell Dam) to reduce the stress on the mussel bed populations though at the risk of increased cost to energy production.

“Mussels lack charisma,” concludes Simmons. “They are not cuddly. They are not our national symbol. Most people see a slimy rock and don’t see the value.”

But if we care about water quality, about fishing, or simply about the natural heritage with which the Ozarks are blessed, it is time to start learning before it is too late.

June 20, 2014

A partial river mussel list:

Spectacle Case Cumberlandia monodonta

Elktoe Alasmidonta marginata

Slippershell Mussel Alasmidonta viridis

Flat Floater Anodonta suborbiculata

Clylindrical Papershell Anodontoides ferussacianus

Rock Pocketbook Arcidens confragosus

White Heelsplitter Lasmigona complanata complanata

Flutedshell Lasmigona costata

Giant Floater Pyganodon grandis

Creeper Stophitus undulatus

Salamander Mussel Simpsonaias ambigua

Paper Pondshell Utterbackia imbecillis

Three ridge Amblema plicata

Mucket Actinonaias ligamentina

Western Fanshell Cyprogenia aberti

Butterfly Ellipsaria lineolata

Curtis Pearly Mussel Epioblasma florentina curtisii

Snuffbox Epioblasma triquetra

Pink Mucket Lampsilis abrupta

Northern Broken Ray Lampsilis brittsi

Plain Pocketbook Lampsilis cardium

Higgins Eye Lampsilis higginsii

Neosho Mucket Lampsilis rafinesqueana

Arkansas Broken Ray Lampsilis reeveiana

Fat Mucket Lampsilis siliquoidea

Yellow Sandshell Lampsilis teres

Fragile Papershell Laptodea fragilis

Scale Shell Leptodea leptodon

Black Sandshell Ligumia recta

Pond Mussel Ligumia subrostrata

Three Horn Wartyback Obliquaria reflexa

Southern Hickorynut Obovaria jacksoniana

Hickory Nut Obvaria olivaria

Bank Climber Plectomerus dombeyanus

Plate 1. Though a beautiful scene, the Bull Shoals Lake impoundment destroyed uncountable numbers of native mussel species.

Plate 2. Rabbits foot mussels. Photo by M. C. Barnhart.

Plate 3. Pink mucket shells, laser engraved for tagging purposes, in pizza box storage.

Plate 4. Snuffbox mussels. Photo by M. C. Barnhart.

Plate 5. Vintage crow hooks used to catch river mussels by the millions.

Plate 6. Neosho mucket. Photo by M. C. Barnhart.

Plate 7. The stunning beauty of river mussel species is apparent to those patiently engaged in their biology. Photo by M. C. Barnhart.

Plate 8. Pebble-rolling logperch play right into the plans of certain mussels.

Plate 9. The powerful, crushing jaws of the freshwater drum.

Plate 10. Open river mussel shells reveal pearlescent beauty.

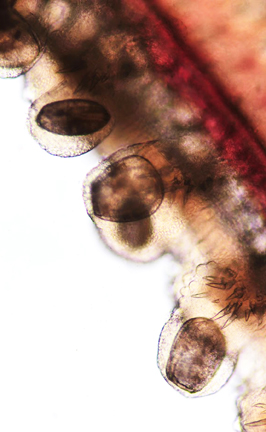

Plate 11. Developing glochidia nestled in the nutrient-rich gills of the bluegill. Photo by M. C. Barnhart.

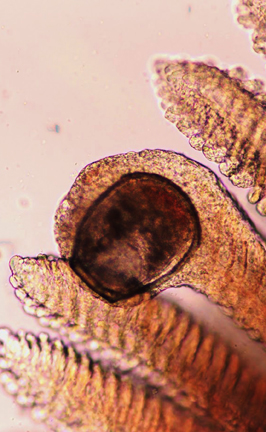

Plate 12. Glochidia detail. Photo by M. C. Barnhart.

Plate 13. Glochidia shown in their blood-rich gill environment. Photo by M. C. Barnhart.

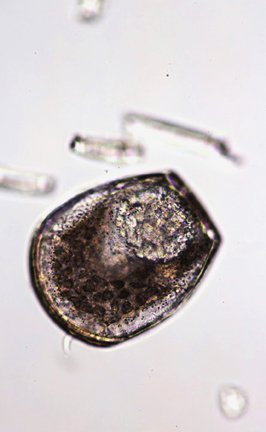

Plate 14. An emerging glochidia, preparing to drop from its fish host. Photo by M. C. Barnhart.

Plate 15. The tiny glochidia is now taking the shape of a river mussel. Photo by M. C. Barnhart.

Plate 16. Although parasitic, the feeding glochidia do not seem to damage their fish hosts. Photo by M. C. Barnhart.

Plate 17. Glochidia freed from its fish host. The tiny animal will fall to the bottom of the river and begin to grow. Photo by M. C. Barnhart.

Plate 18. “Baby” pink muckets grown in MSU’s restricted access aquatics lab.

Plate 19. More developed muckets will be transported to the lagoon at the Kansas City Zoo where they will finish their young growth cycle, then be tagged and introduced into Ozark rivers.

Plate 20. A largemouth bass in the aquatics lab of MSU.

Plate 21. Bull Shoals Lake from Drury-Mincy Conservation just south of Kirbyville, Missouri.