plate 1.

Murder Rocks

by Joshua Heston

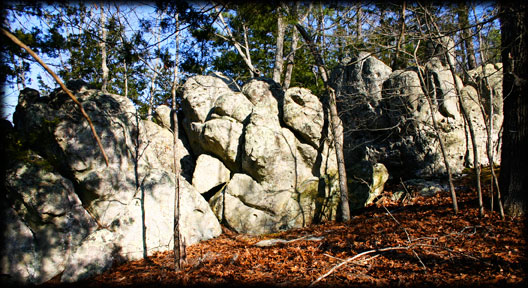

Partway up Pine Mountain, just a few miles south of Kirbyville, a stand of elephant rocks rise to the west of the old Springfield-Harrison Road. Nowadays, they are hard to see (the elevation of the new road took care of that) and harder to get to (they are on private property, so don’t go trespassing).

Elephant rocks — the big outcroppings of sandstone exposed as the rest of the mountains weathered away — are not uncommon in eastern Taney County. These particular rocks, however, have a darker history than most.

plate 2.

It was during the War Between the States.

The conflict tore apart the Ozarks. Most able-bodied men were conscripted to fight (either by the Union or the Confederacy), leaving behind women, children and the elderly. With few armed men to protect farms or folks, bushwhackers attacked the weak and defenseless, stealing livestock and supplies, killing those in their way.

Of all the bushwhackers, none garnered a greater reputation for brutality than Alf Bolin, originally of Spokane, Missouri. An orphan raised by the Bilyeus, Bolin was called the cruelest man alive. At one point, he would return to his adoptive family, threatening to kill Old Man Bilyeu.

Alf Bolin’s victims included 16-year-old Dave Titsworth of Walnut Shade, 12-year-old Bill Willis (shot and killed as he was climbed over a fence north of Garber), James Johnson (brother Wood Johnson, the presiding judge of Christian County), Bob Edwards of Bluff and an 80-year old man named Budd who was forced off his wagon and into the White River near Hensley’s Ferry, then shot.

The Bolin Gang proved able to outride any Union soldiers sent to arrest or kill them. And, although they ranged throughout the region, their activities centered around a certain outcropping of elephant rocks south of Kirbyville.

Murder Rocks.

The huge sandstone formations made a perfect ambush point — an ideal location to watch wagons trundling up Pine Mountain. A huge cleft between the rocks could easily hide 20 men out of sight from either approach. Nobody knows how many men died at these rocks, their wagons torn apart, their property stolen.

Even today, the old ruts of the original road still exist, now grown up in cedar and sassafras. A foot trail leads from the new road down to the Rocks. Trespassers have littered the ground with beer bottles. On a mountain now overlooking the family-friendliness of Branson, the place’s history of death, of murder, of abject brutality, should seem far away.

It does not. There is a solemn air here, a pervasive eeriness. Men died needlessly here, satisfying the greed and debauchery of those willing to murder and rape without apparent concern.

Here at Murder Rocks.

plate 3.

But the Bolin Gang’s reign of terror could not last forever.

Union soldiers realized they could not capture Alf Bolin directly. Douglas Mahnkey (whose 1968 autobiography Bright Glowed My Hills is well worth reading), wrote, “[Alf Bolin] and his band were hard riders as well as good woodsmen; he knew all the trails, all the mountain passes or gaps, all the caves, every ford on White River. He knew how to elude the best of the calvary....”

Instead, a trap was planned: Union soldier Zack Thomas was chosen for the mission. He would travel southward — unarmed and disguised as a wounded Confederate soldier — to Layton Mill on the Arkansas-Missouri state line (and just south of Murder Rocks). There he would lay in wait, pretending his injuries prevented further travel. Now Layton Mill was tended by a woman in a unique and desperate position. Her husband, a Confederate soldier named Foster, was in jail in Springfield and yet Mrs. Foster was a Union sympathizer. Also, the Bolin Gang regularly stopped at Layton Mill to eat at Mrs. Foster’s table.

On February 2, 1863, Alf Bolin showed up for dinner. The killer and his assassin were seated across from each other next to the fire. Mrs. Foster served ham, potatoes and green beans. After eating, it seems, Bolin leaned over to the fire to light his pipe. Zack Thomas struck or stabbed him with a colter, a steel blade used to connect the beam of a horse-drawn plow. When Alf Bolin regained consciousness, Thomas stabbed him again and again.

Alf Bolin was dead.

When word got out, the good folks across the old hills of Taney and Christian Counties celebrated. Soldiers came to transport Bolin’s corpse to the Union Army camp in Ozark, Missouri. But remember, it was 1863. Travel was slow. By the time the corpse had been hauled by wagon to Forsyth, it had begun to rot. Colbert Hays, it is recorded, took an axe and chopped off Alf Bolin’s head. His body was buried just up the Swan Creek road and “south of the Taneyville-Dickens Road, just beyond the forks.”

Alf Bolin’s head was taken to Ozark where it was placed on a pole in the town square for public display. Although the bushwhacker’s evil had ended, it was not the end of danger and unrest in these old hills. Renegades would continue to prey on the population. Some 22 years later, the Baldknobbers would organize to protect women, children and the elderly from outlaws.

The Anti-Baldknobbers would then be organized to protect folks from Baldknobbers-turned outlaws. And in 1889, the last of the renagade Baldknobbers would be hanged, also on the town square of Ozark, thus ending a long, dark and bloody chapter of Ozark history.

Editor’s Notes & References:

Douglas Mahnkey’s 1968 work Bright Glowed My Hills is a significant contribution to Ozark literature. In the book, he assembled a remarkably cohesive history of Bolin and his demise. Mahnkey should know. He was born near Swan Creek north of Forsyth.

“Uncle Sam Boswell was about 12 and lived in Forsyth at the time this happened. He was old, almost blind, when I visited him more than 30 years ago and made the notes for this story,” Douglas Mahnkey wrote in 1968. I’ve yet to find a resource on the history of the Bolin Gang that does not directly reference his book. Mahnkey, Douglas, Bright Glowed My Hills, The School of the Ozarks Press, Kirbyville, Missouri 1968.

Also of importance to the telling of this story is the Bittersweet article “Who The Heck Was Alf Bolin?” written by Vickie Hooper and published in Volume X, No. 3, Spring 1983 issue of that periodical. Bittersweet, Who The Heck Was Alf Bolin?, Volume X, Number 3, Spring 1983.

September 26, 2010