plate 1. “Coming Storm.” Photo by the Missouri Conservation Commission, 1956. Provided by Joanie Stephens of Reeds Spring..

Ozarks Photography

by Joshua Heston

“At the time of the photo,” writes Joanie Stephens, who worked with Jim Owen in the last few years of his life, “Table Rock Dam had been under construction for almost two years. Jim put up a good fight against the dam because it would change the White River. In Jim’s letter edged in black, he mentions the White River was his ‘bosom pal for 25 years.’ As I looked at that picture again, I could imagine Jim grieving one more time.”

“As I looked at that picture....” More than just collections of pretty images, photography is a powerful force, artistic, social, even political. These Ozark hills have more than their fair share of talented photographers. It is with great honor to begin their showcase here...

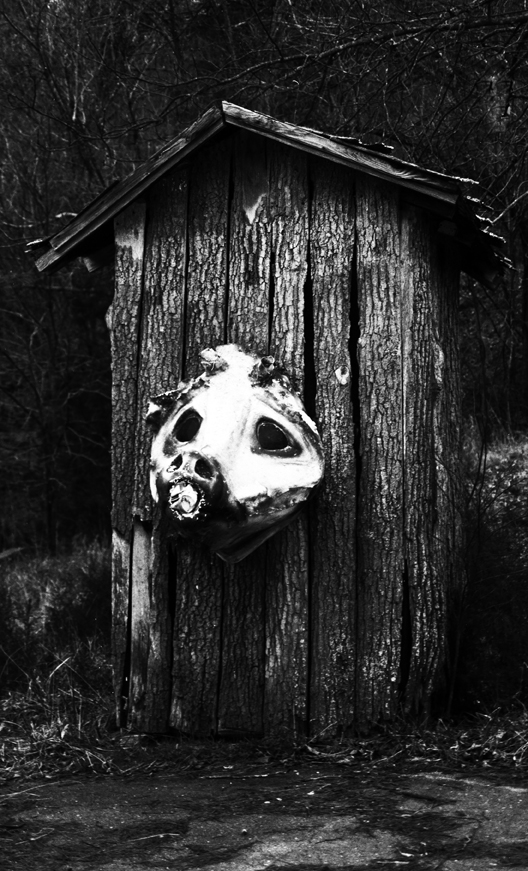

plate 1. Sad Mule, Dogpatch USA by Tenille Blair-Neff.

Dogpatch USA: A Reflection

by Tenille Blair-Neff

It was a cool, cloudy October morning in the year 2000. My little sister and I sleepily shuffled into the car and set off on an adventure. Growing up in the shadow of Joyland — an old amusement park in Wichita, Kansas — had instilled in us a taste for that potent mixture of thrill-seeking and historical decay. Each night we fell asleep to the sound of locusts mixed with that of screams as people flew down the drop of a rickety wooden roller coaster. Many a night I awoke in a flop sweat, having dreamed of a terrifying clown who played the piano at the park entrance.

plate 2. Circus, Dogpatch USA by Tenille Blair-Neff.

plate 3. Waterfall, Dogpatch USA by Tenille Blair-Neff.

It was this shared experience motiviating our road trip to the long-abandoned Dogpatch USA near Jasper, Arkansas.

At the time I was a 22-year old art student visiting my family who had recently moved from Wichita to Branson. My sister had learned of Dogpatch from some new friends and we were eager to explore. I brought along my 35mm black-and-white camera and hoped to get some good shots for my photography class. The drive was long. We spent most of the trip singing along with The Cure, all while cracking witty jokes.

We were young, melancholy and full of diffuse energy.

plate 4. Razorback, Dogpatch USA by Tenille Blair-Neff.

plate 5. The General, Dogpatch USA by Tenille Blair-Neff.

We arrived at our destination and climbed an old fence. The place looked more like a wooded farm than an amusement park. There was a deadly calm; the still air cloaked with eerie silence. I will never forget the cracked concrete, broken by thriving vegetation beneath its surface.

It is comforting to realize our human efforts to control nature are merely temporary. Life has a way of bursting through our strongest attempts at containment.

The abandoned park was littered with fallen statues of old childhood heroes. Their once joyfully painted smiles were weathered, beaten from years of exposure to the elements. I marveled at the contrast between what the park had once been — and what it had now become.

plate 6. The Kiss, Dogpatch USA by Tenille Blair-Neff.

plate 7. Hillbilly Bee, Dogpatch USA by Tenille Blair-Neff.

plate 8. Fallen Man, Dogpatch USA by Tenille Blair-Neff.

Little did I know that year would mark the end of my own childhood. In the following months, I would graduate, get married and move far away from everything that held significance in my life. The period of life to come was, in some ways, an attempt to abandon whom and what I was before.

It was a time to invent a new life — one that left out the old roles I had played. As I prepared these photographs for State of the Ozarks magazine, I couldn’t help but notice the passage of time has brought me back to the very place I had tried to escape.

Recently I’ve moved closer to my family. I’ve come to realize all my attempts to contain my true self failed, as if my nature has burst through the concrete of my own well-crafted defenses. Today, as I breathe a sigh of relief, I know I’ve come full circle.

Our heroes rise and fall. Our innocence is lost but then reborn in our children. The ruins become like Dogpatch: a sad and comforting homage to the temporal nature of our lives.

October 30, 2014

Tenille Blair-Neff serves on the Branson Arts Council Board of Directors and is a practicing psychotherapist with 13 years experience as an artist in New York City. She currently resides near Blue Eye, Missouri with her husband Joel Neff and their young son.

plate 9. Hogshead, Dogpatch USA by Tenille Blair-Neff.