Branson Past & Present

by Joshua Heston

Deep in the White River Hills lies now world-famous Branson, Missouri. Touted as the live music capital of the world, the city has more theater seats than Broadway, over 200 hotels, 13 golf courses and more than 400 restaurants.

We’re also home to a long stretch of blacktop known alternatively as the 76 Strip, 76 Country Boulevard, or the “world’s longest parking lot.”

Crowds of vacationers have come here for generations, making smalltown Branson (founded in 1913) a uniquely Midwestern tourist hotspot located not in the Midwest but rather in the once isolated, rustic and rugged far western mountain plateau of the American South.

Branson is a town constantly seeking definition — and redefinition. Is hillbilly culture real? Is the term “hillbilly” a compliment or an insult? Is Branson a cultural hub of the Ozark Mountains? Or is the town simply a regional tourist trap?

The most honest answers are “Yes,” “No,” “Both,” “Neither,” and “So much more,” but not necessarily in that order.

For what was once an unheard-of mountain town, the history and story of Branson confounds us. Beneath the traffic jams, the “Sell Your Timeshare Now!” signs and the influx of people from all corners of the globe, there is a rich and at-time dark tapestry of history, culture and conflict.

Long ago, these river bottoms and rugged treeless mountain tops called “bald knobs” were home to ancient First Nation cultures: the Mississippian Caddo (who were ravaged by DeSoto’s troops) and the Osage, a uniquely civilized people of Lakota ancestry, feared for their warriors and who, upon first encountering Europeans, found the “superior” race to be short, ill-mannered and bad-smelling.

After the United States’ founding, the federal government would relocate the Tidewater Delaware people to the Ozarks, moving them off then-valuable land in the east and into the dark, isolated interior — a rugged inland mountain range apparently thought to be unusable. When rumors of silver circulated through the hills — and when more and more settlers found their way into present-day south Missouri — the Delaware were again forcibly resettled.

A subsistent, but structured, pioneer life developed here in these White River Hills. Ridge-top and river bottom communities were built. Trade routes established. Old buffalo trails became roads, albeit small, windy, rocky, muddy roads. And the White River — which present day tourists see as Lake Taneycomo and the vast reservoirs of Table Rock, Bull Shoals and Beaver Lakes — became a road as well. Keelboats and even small steamboats plied the river when conditions were right.

Most settlers, it seems, were of Scots-Irish ancestry and typically migrating from Kentucky and Tennessee. But in the 1860s, what was a hardscrabble but relatively peaceful life turned dark, bloody and terrifying. The Civil War raged throughout the Ozarks, not in the form of magnificent battles between regimented soldiers but instead a civilian war. Guerrilla warfare devastated the mountains. The White River Hills around present-day Branson were a hotspot of the war. Crops were destroyed. Livestock killed. Mills were burned. Families murdered.

It was the beginning of a desperate era.

Despite a formal end to the war at Appomattox, Virginia, the conflict — in the form of bushwhackers and outlaws — continued to ravage the people here in Missouri and Arkansas. The hills became a no-man’s land where law and order ceased to exist. And it was in this atmosphere of lawlessness the Baldknobbers — hooded vigilantes named for their meetings atop the treeless mountains — were formed. The vigilantes rode out on night raids, threatening, then lynching, shooting or stabbing troublemakers. In time, Anti-Baldknobbers were organized, vigilante groups to oppose vigilante groups. All this began in nearby Kirbyville and Forsyth, just a few miles east of present-day Branson, and spread elsewhere in the hills.

A mountain culture, weary of bloodshed, steeped in the traditions of the Scots-Irish and Appalachian cultures, and largely isolated from a larger world changed by the Industrial Revolution, was guarded. Distrustful of strangers, proud of their ancestry and the simple fact they had survived when others had not. At the same time, a lack of good roads and the always-rugged terrain kept the Ozark Mountains fenced off from progress. The Ozarks became a haven for outlaws. Jesse James would hide out in the Missouri hills. A generation later, so would Bonnie and Clyde.

Strange superstitions, folklore and ways of life reminiscent of a much older — even Elizabethan time — prevailed.

American author Harold Bell Wright found inspiration in the hills and hollers of Taney County and his best-selling book The Shepherd of the Hills was penned. Something of an American Romanticist, Wright found profound inspiration in what was otherwise regarded as “backward” hillfolk. He wrote of a deep nobility of the people. His heroes were the beautiful Sammy Lane and the brawny Young Matt as they struggled with questions of self-worth, the meaning of compassion, the value of faith and chivalry, all against a rustic mountain backdrop of vigilante justice and family loss.

The book transformed Wright’s career. Shepherd of the Hills also transformed the local communities. Published in 1907, it was not long before tourists came wandering into the country to see if they could find the real-life Sammy Lane and Young Matt as well as other characters in the book.

A railroad line was built. Branson itself founded in 1913. The people began to come.

It is ironic as Wright even lamented a time and place when these hills would no longer be isolated. He wrote, “Before many years a railroad will find its way yonder. Then many will come, and the beautiful hills that have been my strength and peace will become the haunt of careless idlers, and a place of revelry. I am glad that I shall not be here.”

Ironic indeed, for the stories of Wright’s book brought the people, transforming Branson — in the course of a hundred years — into a vast network of parking lots, billboards, bright lights and the debris from eight millions tourists annually.

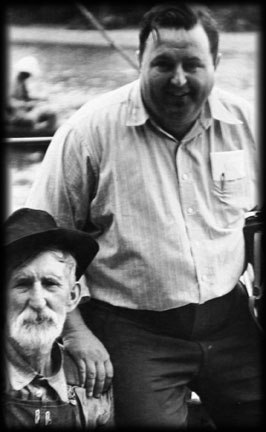

Following the publication of Shepherd of the Hills, the damming of the White River at Powersite (1913) would strengthen the burgeoning tourist trade at Rockaway Beach. Float trips on the James River and the White River (now present-day Table Rock Lake) flourished and Jim Owens became a local celebrity for his exuberant, larger-than-life personality, his business acumen, and his knack for bringing big-name celebrities into the Ozarks to partake in his float trips.

The White River remained largely untamed however, and in 1943 the lake / river flooded much of downtown Branson, Hollister and even destroyed the steel bridge that spanned Lake Taneycomo from Main Street to Mount Branson. Plans were finalized for the creation of Table Rock Lake, a man-made reservoir which would inundate over 43,000 acres of private land. For some, it was a welcome step into the 20th century. For others, it was big government running roughshod over the common man.

The dam was finished in 1959 and the lake brought more new development. Many hill folk warily observed an influx of “lake people,” new urban settlers from places like St. Louis, Kansas City or Little Rock, bent on developing the shoreline and establishing modernity.

A year later, Silver Dollar City opened as a humble “mountain village” over the top of Marvel Cave, a long-time tourist attraction ever since the Marvel Cave Land & Mining Company had dug all the bat guano from its seemingly endless depths.

Near Dewey Bald, a mountaintop featured prominently in Wright’s book, the outdoor amphitheater Shepherd of the Hills also opened. The cast was made up of local folks, including Don Bilyeu (pictured at right). These were people who spoke like the characters in the book not because of acting lessons or professional training but because that was who they were:

Hillbillies marketing a unique culture — and the raw honesty resonated with tourists increasingly removed from the simpler things in life.

This was the 1960s. It was an age of atomic energy, social unrest, the space race, and an unknown destination. Americans didn’t know if we were hurtling toward a shiny, plastic-laden future or to a social — or literal — Armageddon. The simplicity and security of a past time held great appeal.

And that appeal resonated not only in the fishing, the craftsmanship and the beautiful scenery, but also in the music. The Mabe family, joined by Chick Allen who could tell of his own Delaware Indian heritage and often played the jawbone of an ass, had begun playing “hillbilly music” interspersed with comedy in downtown Branson in 1959. The name the family group chose was already tied to these hills:

The Baldknobbers.

A Branson family dynasty was established in 1967 when the Presley family opened the first show on the 76 Strip, then miles out of town on the winding road leading to Shepherd of the Hills and Silver Dollar City.

In 1973, hometown Branson history was again made when the Plummer family from Knob Lick, Missouri (in the St. Francois Mountains near Farmington) moved to town and opened theater number three. Combined, these three families forged the quintessential “Branson show,” a two-hour live music extravaganza filled with country music, cornball comedy, Chet Atkins-style guitar licks, some bluegrass instrumentals, a patriotic nod to our troops, Southern Gospel-style quartet singing and a show-stopper like Mule Skinner Blues or the fiddle tune Orange Blossom Special.

It is a formula that has lasted now several generations.

Some still regard the ’70s and ’80s as a golden era in Branson shows. The Strip was packed with cars (partly because there were no alternate routes). Townsfolk and entertainers knew each other well and the season lasted only from May through October. The city's offerings were filled out with places like the Mutton Hollow Craft Village, Shad Heller’s Toby Show, the Sammy Lane Pirate Cruise, the smooth quartet singing of the Foggy River Boys, the Bob-O-Links Theatre (founded by former Baldknobber Bob Mabe), and Chisai Child’s Starlite Theatre, among others.

But on December 8, 1991, the unthinkable happened. CBS Nightly News featured Branson, inferring it was an inexplicable country music goldmine. A number of country music stars had already landed here by that time, including Roy Clark, Moe Bandy, Mel Tillis, and Ray Stevens, spurring the report.

“The billions were pouring in,” said CBS correspondent Morley Safer.

Unprecedented growth occurred as investors — and scam artists alike — invaded Branson, selling dreams to hopeful music artists and unwary tourists. The changes brought needed improvements to the city’s infrastructure but gone were far too many trees and hills. Some companies have proven invaluable to our town, like the long-running Dixie Stampede as well as Legends in Concert and the museum attraction Titanic Branson (all three companies operate similar attractions in other locations).

But there was a darker, more complex side to the success which became all too apparent when the economic recession of 2008 hit. Branson had been overbuilt, with too many hotels, too many restaurants, and too many time share companies bilking tourists for the right to stay in too many condos. Many motels turned into “long-term stay” facilities and became hidden housing for a growing population of indigent people. And while mainstay businesses like Presleys’ and Silver Dollar City forged ahead, many places closed up shop for good, unable to obtain another line of credit in a suddenly conservative economic market.

In 2012, the Leap Day Tornado added another dimension to Branson’s recovery. In the early morning hours of February 29, an EF2 twister roared across the Strip, tearing apart various structures. While many locations were not hit, squabbles with insurance companies left semi demolished buildings sitting for months, giving the otherwise functional town a constant reminder of the damage.

Now two years later and beginning yet another entertainment season, the question of Branson’s at-time surprising success and challenges continue.

Perhaps the irony of our tourist influx is more complex than originally thought — and in the end redemptive to the Ozarks.

Harold Bell Wright’s book, celebrating a unique hill folk culture, transformed this land by an influx of visitors, people looking for “real” hillbillies and expecting to find a certain set of values, traditions, crafts, art and music. The locals responded and that response kept those traditions alive from generation to generation as old ways died out elsewhere. There is an awareness here, a sense of place, an appreciation for that intangible “Ozarks” at times just out of reach.

Hillbilly culture may be hard to define but easy to recognize:

An appreciation for the simpler ways of life. A rugged independence, hospitable but distrustful of strangers. A bond with nature, inner nobility and with the old ways that holds fast against the onslaught of modern culture and media. A deep appreciation for the old traditions, the stories, the songs, and the craftsmanship.

Ours is a complex story, one that is still in the telling.

March 27, 2014

Source Citations:

Chandler, Arline. The Heart of Branson, History Press, Charleston, SC 2010

Hartman, Mary and Elmo Ingenthron. Baldknobbers: vigilantes on the Ozark frontier, Pelican Publishing Company Inc., 1988

McGill, Bob, Branson’s Entertainment Pioneers, White Oak Publishing, Reeds Spring, MO 2007

Wright, Harold Bell. The Shepherd of the Hills, The Shepherd of the Hills Historical Society, Inc., 1907

plate 1 (top). Vintage photo of Old Matt’s Cabin at Shepherd of the Hills Homestead. Photo courtesy of John Fullerton. Original photo by Townsend Godsey.

plate 2. Traffic always backs up on 76 Country Boulevard, especially as evening show times near. July 4, 2008.

plate 3. Souvenir bargains and power lines frame the theater district of Branson. July 4, 2008.

plate 4. A beautiful spot below Table Rock Dam showcases a view reminiscent of the untamed White River in an earlier age. May 27, 2010.

plate 5. William Powell (at left) started one of the first steam powered saw mills in the area. His mill shown here was located along Fall Creek. John Ross (at right) is remembered as Harold Bell Wright’s inspiration for the Shepherd of the Hills character “Old Matt.” Photo courtesy of Talking Rocks Cavern.

plate 6. Just another sunset in the hills, photographed just east of Branson in the Drury-Mincy Conservation Area. October 28, 2011.

plate 7. A boater plies the waters of Lake Taneycomo. A cold-water lake since the creation of Table Rock Lake, Taneycomo is a leading trout fishery. June 15, 2012.

plate 8. The monolithic Table Rock Dam dominates the scene and Branson’s history. Besides inundating thousands of acres of private land and forever changing the landscape of the White River, Table Rock Lake brought the tourists — initially in the form of bass fishermen. May 27, 2010.

plate 9. Larger-than-life Jim Owens (right) pioneered commercial float trips on the White River. Photo courtesy of the Ralph Foster Museum, College of the Ozarks.

plate 10. Swimmers play at Moonshine Beach on Table Rock Lake. May 27, 2010.

plate 11. “Collector knives, windsocks, flags for $5 and Branson souvenirs for $1,” read the signs. July 4, 2008.

plate 12. Silver Dollar City’s Red Gold Heritage Hall. Affectionately and simply called “The City” by Branson locals, the theme park works hard to portray an Ozarks past in a beautiful, idealized way. October 11, 2008.

plate 13. Don Bilyeu, Ozark native, played several characters in the first season of Shepherd of the Hills, including “Jim Lane,” “Lem Wheeler” and “Preachin’ Bill” back in 1960. He currently resides with his wife Shirley on their cattle farm near the Finley River in Christian County. July 18, 2009.

plate 14. Chick Allen at Silver Dollar City. Photo courtesy of John Fullerton.

plate 15. Baldknobbers at Silver Dollar City. Photo courtesy of John Fullerton.

plate 16. Branson’s original show on the strip, the Presley family have a proud history as leaders in the town’s entertainment. July 4, 2008.

plate 17. Grand Country Square, built where Branson’s first Wal-Mart first sat, is another leader in the city’s unique, country music scene. June 8, 2008.

plate 18. An evening performance at the Shepherd of the HIlls outdoor drama. October 10, 2013.

plate 19. Not far removed from the bright lights of the Strip, the Sycamore Church still opens its doors every Sunday, only a few miles north of Branson. August 4, 2009.

plate 20. The pottery of Tracy Adams, originally of Kansas, displays the warmth and craftsmanship many visitors expect from the Ozarks. October 3, 2009.

plate 21. A hillbilly caricature by Harold Enlow of Harrison, Arkansas, appears to wink. April 18, 2008.

plate 22. Black Oak Ridge, as seen from the parking lot at Silver Dollar City, display the unique, rugged, indefinable draw of these old mountains. May 4, 2008.