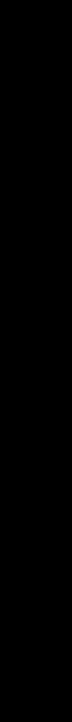

plate 1. Walker Powell in his home, nestled in the Ozark Mountains, near Talking Rocks Cavern.

Walker Powell (Part 1)

(transcription by Joshua Heston, interview by Jody Gertson of Talking Rocks Cavern)

Do you want me to tell you the truth? I’ll tell the truth as far as I know. I could make up a story and I guarantee you’d believe it. People are very gullible. I could take my slides and make up a story and they’d believe it.

My father was born in Lamar, Missouri (pronounced Missour-ah). Ralph Waldo Emerson Powell. That was his full name. His mother was a fan of Ralph Waldo Emerson. That’s where he got the name. He went by Waldo or Wally. Wally was his name his friends called him. Just Wally. That’s how he wound up in the Shepherd of the Hills as “Ollie.”

My grandfather was born in Mt. Palatine, New York. It’s a little old place in New York. [How did your grandfather move to Missouri? ] Well, I’ll have to start way back during the Civil War. When he got out of the Army in 1864-65, why, he went to Carthage, Missouri. He was just married and he took his family. He stayed there awhile and he tried to get into the dry goods business but it didn’t work. So there’s two newspape’rs there and he applied at one and got a job. And worked for them for awhile. And then went over to the other newspaper and they hired him and he learned the printers’ trade by doing that. So he stayed there a couple of years and then he found out there was a paper in Lamar, Missouri, for sale. So he thought he’d go there and see if he could buy it. And he run onto a young fella working for the paper there by the name of Levi Morrill and they got their funds together and bought the paper out. It was called the Lamar Advocate. That was a kind of a Democratic paper. So he changed it to the Barton County Advocate.

He stayed there about 10 years and his health got kind of bad. He went to his doctor and his doctor told him. “You got to get out of this office. You’re spending too much time in there. You got to get out in the open." So, of course, during the Civil War he had done a lot of camping and hiking and everything so he hired him a buggy and a horse and he started down — he heard about a cave down in Stone County. And he was interested in caves. He found a cave up in Carthage, Missouri. A huge cave. And they explored it. And he wrote, after he got down in Stone County, he brought his equipment with him and he established the first newspaper in Galena, Missouri, in Stone County. He homesteaded down here. He came down here first and later he liked the place so much he decided he would move down here.

So he went back to Lamar and he talked four or five of his Union soldier buddies into investing in that cave down here. So they formed the Marvel Cave Land & Mining Company. They were looking for lead or silver to make money out of. And the only thing they found to sell was bat guano. That’s bat manure. There was a great big pile of that right under the entrance to the cave. So they started mining that out there. They built a thing they could pull the stuff out with a horse and it would sell for $750 a ton. Its high fertilizer. That was good money back in those days though it ran out in about six years. They had all the guano out so the men went back to Lamar and said [to Truman] "You can do whatever you want. Just sell it and get whatever you can out of it." See, each one of them had put in about $1,500 to start out on. So he kept it a few years and then a man come along and said he was interested in buying the cave. And he said, "Well, how about $7,000 and I’d consider it. And this was a man by the name of Lynch. So, Lynch bought the cave and that section for $7,000. Well, he kept it a year or so and his brother came down and he liked that place down there. So he said, "I’d like to buy it." So William Lynch said, "Well, $10,000 would" — William was the brother, and he sold it to this man for $10,000. [So] the brother turned around and sold it to his brother for the cave. And that’s how he got ahold of Marvel Cave.

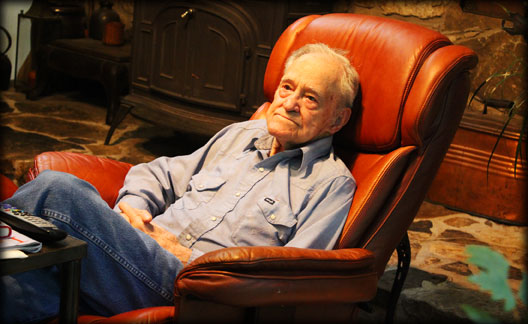

plate 2. Waldo Powell in the original entrance of Fairy Cave, later renamed Talking Rocks Cavern.

My father is the one that had Fairy Cave. My grandfather was the first explorer in Fairy Cave. He and his oldest son was the first two that went down and then there was four or five other men followed them down. They built an old-fashioned windlass over the entrance because there is a 90-foot drop down to the bottom to the cave. So they tied a stick to this rope and they’d hold onto the rope and they’d lower them down slowly. And of course the first time they went in there my grandfather got down about halfway and he hollered [to stop] and they thought there was something wrong so they said, "What’s the matter Mr. Powell?" He said, "I want to just stop here for a minute and look at the beauty of this cave. Its unbelieveable." They lowered him on down. They thought maybe he’d got sick or something. So those six men stayed in there about four or five hours exploring the cave. That was the first exploring trip, 1896. Later there was a lady by the name of Luella Owens who was [writing a book] about the caves in the Ozarks and the Black Hills. And she heard about Marvel Cave through my grandfather so she wrote him a letter asking if she could come down and go into that cave. And he said sure. So they still had the old windlass.

plate 3. Two loads of crossties. Oak was the primary building material for rail ties and was a top export during the railroad years. Oak posts could last untreated for 15 to 20 years. Each tie was hewn by axe and sold for 50¢ apiece. Two men could harvest a load of 12 per week (the profit of $6 would then be split 50/50).

He went over to the mill. Uncle Will had a sawmill and they gathered around on Saturdays to have their grain ground (their corn and their meal) and they’d sit around and talk and gossip. That’s where Harold Bell Wright got a lot of his stories about the Shepherd of the Hills, listening to these men talk. It took some time before the local men accepted Wright as they supected he could be a government revenuer.

So this Luella Owens wrote in her book what a terrible trip it was from Grandpa’s place over to this cave [Fairy Cave]. She said it was nothing but an old trail and it was rought and they just had an old buggy. So they drove up to the top of the cave and there was a house there so they stopped and she walked on down there over the hill to where the cave was. And the men were already down there getting ready to go down in the cave. And so she said, "Yeah, I’d like to go down." So Uncle Will went down first. And Grandpa went down. And then Luella Owens, she walked up there and she took one look down there and she backed out. She said, "I don’t believe I want to go down there." So she went back and sat under a tree and waited for them to come back out. And they was in there about six hours. So when Grandpa come back out, she went over and she said, "Mr. Powell, what did the cave look like?" He said, "All I can say is it look like an underground fairyland." "Well," she said, "Let’s just call it ’Fairy Cave.’" And that’s where it got its name. She wouldn’t go down there. She backed out.

plate 4. The musical stalactites were a popular part of the Fairy Cave tours. Walker and his sisters would play out tunes like Mary Had A Little Lamb (tones ranged from bass to tenor).

[My grandfather] passed away when I was two years old. My sister would go stay all night with grandma and grandpa. Of course, he taught school there at Notch. It was a one-room grade school. I think he taught there just one year. In the meantime he had the Stone County News Oracle up [in Galena] and he walked back and forth between the homestead — he walked up to what is now 76 and somebody come along and picked him up and would take him on over to Galena. But he’d stay up there about all week and then come back on weekends.

Well, you know I wrote a book about my dad. Jack [Herschend] wanted me to tell about my dad. It took 30 pages for me to describe him. He was quite a character. We spent quite a bit of time together. He liked to hunt. And when I got to be 16-17 years old, he’d take me hunting with him. Of course he couldn’t drive so I had to do the driving. We’d go out to California or Colorado and stay there. He had some brothers in California so we’d go out there and visit them and while we was there we’d go back up in the mountains and pack-back up on horses and spend a week up there just the two of us. Of course he done the cooking and he kept track of where we was at and all that stuff. You never had to wonder what kind of eggs you was going to have. You couldn’t say, "Give me some over easy." Well, they was all scrambled. It didn’t make any difference what you wanted you got whatever he cooked. He was about 60 years old at that time.

See, at that time there wasn’t deer in here [in the Ozarks]. There was no turkeys or anything. Killed out.

[In Colorado or California] We was hunting the mule deer. The bighorns and so on. I brought the head back and he had it mounted for me. It was a 300-pound mule deer. The meat? Well, we had a problem with that. We dressed it all out and he decided he would smoke it. All we had was that old soft wood out there in the mountains and it didn’t taste good. Terrible. But we packed it in a little box and we put it in the back of the car and started home with it and it got to stinking. So we stopped along the road and dumped it. The coyotes probably ate it.

plate 5. Sister Hazel Powell shown ready for a cave tour. The original entrance has been covered by a new stone building.

When I started guiding [at Fairy Cave] I was 17. But I started working at the parking lot when I was about 10 years old. I was putting bumper [stickers] on and I was parking cars because the parking lot wasn’t very big. So you had to be careful how they were parked so they could get out when they got out of the cave. Well, if my dad had a party in there it would take him at least an hour to go through there. Hated to see him get a party because I knew it was going to be a long time before they would move.

Marjorie [Walker’s sister] would go through there in 20 minutes. What they’d do is go down and catch my dad’s party and by the time he got through he’d have about twice as many people because each one would just go down and say, "Now you can join this group here."

[Your sisters sound like they had quite the personalities.]

Well, I guess you could call it personality. My older sister wasn’t very good with the people. She didn’t have much patience with them. Hazel. Now Pansy was really the best. She was the youngest sister and she was a pretty good guide. She’d go down there and she’d play the musical formation pretty good. Like Mary Had A Little Lamb and all that kind of stuff. I was — my parties probably averaged 45 minutes to an hour too. I took my time and I showed all the different things the girls left out. I carried a lot of kids through there. I didn’t want them to fall. I’d rather carry the kids than take a chance on [them] falling. So I’ve carried a lot of young kids through there.

I didn’t guide in there until the concrete stairway. When my sisters guided, there was the old wooden stairway and they had iron pipes for railing. So they just held onto that. But in 1928, they put concrete in there. And they carried kerosene lamps and I guided after they had electricity in there.

I got out of the Army in 1942. I was in the Army 39 months. In the Air Force. I could see that coming on so I went to school and learned how to do air craft sheet metal work and then I got a job in Baltimore making airplanes out there for Martin. Well, I didn’t like it too well. They put me inside of a wing where you bucked rivets only they didn’t give you any hearing [protection] and you’d get out of there and you couldn’t hear anything. I stayed there and about four or five other boys from Missouri just got an old car and come back home. They offered me a five-cent raise. I was making 50 cents an hour so they’d give me 55 cents an hour if I’d stay. I said, "No." I think they had 30,000 men out there. We made the Martin Bomber.

The war, see, had just started, when I got back. I had a friend who sent me to that air force school up in Kansas City. And he went down in Georgia and got a job at a big airfield and he wrote me a letter and wanted to know what I was doing. I said, "I’m at home. I’m not doing anything." He said, "Come on down here. I got a job for you." So I went down to Albany, Georgia. I stayed there practically through all World War II. And when my draft number come up, I told my boss, "I’m going to have to go sign up." He said, "I’ll tell you what to do. You go up to your county seat. You enlist in the Air Force. That’s the best thing you can do." And I said, "Well, what’s going to happen?" He said, "Well, we’re going to bring you right back down here. You won’t be making as much money." Twenty-one dollars a month was what I was getting paid. At that time I was married and my wife got a job at a smaller airfield. We was training bomber pilots. Had two-engine planes. And we was training English and French pilots along with Americans. I stayed there practically all through World War II.

I was stretched out on the depot platform, waiting for a train and somebody come in there [yelling] "Sergeant Powell! Sergeant Powell!" I said, "Here!" He said, "I got bad news!" I said, "What’s the problem?" He said, "Well, you got too many points." You had so many points and you was discharged. So I had a boy at that time and that give me enough points that I couldn’t go overseas.

I didn’t want to go over there and get in that Bomb. They’d just dropped that darned Bomb over there and what we was going to do is go over there and clean up that mess. So I wasn’t looking forward to that. It was good news to me because I had a wife and a child and I was needed at home. My dad was up in years.

plate 6. “White Rock Bluff was one of the prettiest places on the James River,” remembers Walker, “It was all covered up by the lake.”

Home was right on top of the hill. That’s the house I built when I got out of the Army Air Force.

[Stone County] Well, it was a typical hillbilly town. Like Galena and Reeds Spring, they were Saturday towns. Only time you went and bought groceries was on Saturday. [On Sundays] the problem with us we’d have to go five miles to church. Well, you’d have to harness your team and get your wagon ready and it was just too much trouble. About the only time — now a lot of people went to that old brush arbor. That’s what the Pentecostals, if they didn’t have a church or school to go to, why, they’d build one of those in the summertime. You ever go to a brush arbor?

A lot of times there’d be a traveling preacher come through and he’d go to the school house and he’d preach on Sundays. Schoolhouses were never locked. We never locked our houses either. [If people came by] we never turned anybody away. They’d camp right there in our yard sometimes. There was a fella here not too long ago said, “You know what? We camped in your yard years ago. My dad and I.”

The picnic ground was up there where it was kind of flat and level. It was one time an old Indian stomp ground where the Indians had their dances. That was when they had the old wooden stairway in there. I don’t know how they ever got people up and down there. Over at Marvel Cave they’d take like a 14-pound maul and go down those steps and drop that on there and it would sound, you know, and if they’d need to replace it they’d put a new one in there. You hear all kind of crazy things.

plate 7. The original parking lot at Fairy Cave (Talking Rocks Cavern). Walker parked cars for tourists when he was just a boy.

The best year we had was back during the Depression started in 1928 and if I can remember right I think we had 1,500, something like that. The tourist industry back then was from school-out to school-starting: just the summer months. Now we were open the year around but we’d get a few farmers out of Illinois and so on. So we’d stay open year around. I’d take maybe one or two trips in the wintertime.

[Now you served breakfast on your trail rides and chicken dinners on your cave tours?] That’s right. They’d have to order [the meal] before they went into the cave and I’d cook for as many as 12 on the trail ride. Dutch ovens and all that they way you used to do it. I could have pancakes or I could have biscuits and gravy. I made biscuits in a Dutch oven. I made pancakes. Then I had a big coffee pot you know. I boiled my coffee. It wasn’t perked but it was made the old time way.

[Flour, sugar, and tobacco. Salt and pepper]. My dad smoked a pipe. Even a lot of the women smoked back in those days, had little small pipes. My mom never did use tobacco. I smoked a pipe and when I was in the Air Force I smoked cigarettes. And then when I got back my dad said, "I don’t want you smoking cigarettes." So he bought me a pipe. He thought cigarettes wasn’t good for you.

One way they had of making money was bootlegging liquor. Whiskey stills. You could buy your whiskey from these distillers. If they knew how to make it was safe. One way [to tell it was safe] was to shake it up and down to see how it was beading. It was bubbles [and] the bubbles were supposed to be good. I never did drink any of it. One drink of that would burn you all the way down. It was used for [alcohol and medicinal purposes]. It would burn [a sore throat] out, I guarantee it. My dad wouldn’t drink until it got legal. And after it got legal, why, he always took a bottle with us when we went camping and the first thing we’d do when we got up in the morning is take a swig of that and it would warm your stomach up and made your breakfast taste real good. You ought to try that sometime!

What we did, if you got copperhead bit, was take a bucket of kerosene and stick your hand down in there and you didn’t have to get any shots. You’d leave it in there for a few minutes. All you had to have was enough kerosene to cover your hand or foot. You see, Hazel, she got bit by a copperhead and that’s what she done. She stuck her hand down in some kerosene and that done the deed.

July 18, 2013