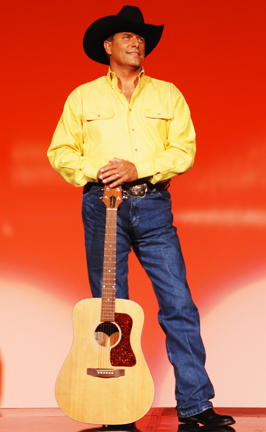

Don Bilyeu

by Joshua Heston

“People have a little, mistaken idea due to Hollywood and other places, about a hillbillly,” says Don Bilyeu. “But I am a hillbilly. And the hill people: they had a creed. They were the most honest, caring people. And they took care of each other.”

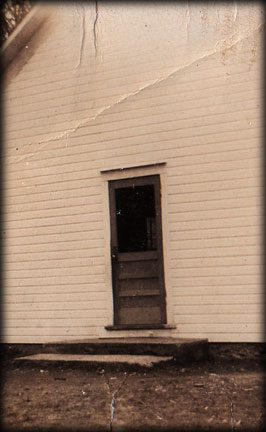

Don Bilyeu was born in 1938 and raised in the Bull Creek Community between Branson and Ozark, Missouri. He went to school at Enterprise, a one-room school with eight grades.

Don has witnessed a lot of changes in Ozark Mountain country. Recalling traffic on Highway 65, back when it still ran through Highlandville, “There were some winter days you could sit and watch all day and only see one car go by.”

Straightforward, yet tempered with grace,” says Elias Tucker, “Rugged in character but as gentle and soft-hearted a man as you’ll ever want to meet.”

Don, with wife Shirley, farm a 125-acre farm near Sparta, Missouri. Don also works for the City of Ozark. They are members of the Smyrna Baptist Church.

And it is an honor to include his recollections here on StateoftheOzarks.

August 15, 2009

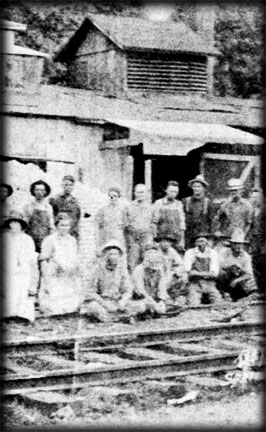

Tomato Cannery of Reeds Spring

from Don Bilyeu

I don't care about a canned tomato to this day.

It was a revolving table that went around all the time. I remember this one — it was a truck, a big truck — big, two-ton, long wheel-base, flatbed truck that came out of Arkansas.

And he’d always bring crates of tomatoes to sell. But then he would also have a load of the stoutest women I ever saw in my life.

Out of Arkansas.

Big women — big, strong women. I guess they split rails or something the rest of the time. But they would come and they’d peel. And each one of them — each woman that was peeling — was assigned a number.

And they’d have three buckets with that number on it.

And as the tomatoes would come around to the fella where they scalded them, where they could peel them, they’d dip that bucket up as it went around.

Then the woman would peel out of that bucket into another bucket. And that’s the way they got paid, by the pound.

And my job was to weigh them buckets as they come around. I’d take the bucket off and weigh it, and then a fella there by me would take it and dump it into the canner.

And there was a woman that set there and she wrote down the number and how much it weighed.

But the women wouldn’t scatter them out. It was just a big conveyor, but the buckets might come around — three or four that wouldn't have anything — and then there’d be all of them just tight as they could get them; all together right there.

Well, we couldn’t get them all off.

You could get part of them, but you couldn't get all of their peeled tomato buckets off. Well, if you didn't get their bucket off and it went back on around, pretty soon they run out of tomatoes to peel. And they’d just have to stand there. They wasn't making no money. And it would make them awful mad.

Oh, it was hot in there. Steamy and just terrible hot. And once in awhile, a woman would pass out. They'd drag her out. I seen this big woman — she jumped that conveyor. And they used what they called a tomato spoon. It kinda looked like a teaspoon, but it was sharp as a razor. And they'd core the tomatoes with it.

She jumped that conveyor belt. She come over there and she grabbed me by the shirt and picked me plumb up off the ground. She stuck that tomato spoon up there at my throat and said, “My bucket come by one more time, I'm cutting your throat.” That old kid that dumped them was standing there he kinda laughed and she grabbed him.

I asked her, “What number is your bucket?” And she told me and then she left. And he said to me, “What number did she say her bucket was?” And he was white as a sheet. I told him. And he said “I'll help you watch for it.” But it was 75 cents every hour. That was pretty good money back then.

— December 14, 2008

plate 1. Don Bilyeu.

plate 2. Enterprise School, courtesy of Don Bilyeu.

plate 3.

plate 4. Reeds Spring, tomato cannery, circa 1925. Photo from Chick Allen.

plate 5.

plate 6.