Soundly Unlawful

by charles Morrow Wilson (a book excerpt)

I liked the brothers enormously. Noah had been the perennially promising member of the family. He was a gentleman, hard working, studios, even scholarly. Brother Sody had been the happy go lucky member with chronic leanings toward daydreaming and sitting down. The same autumn that Noah went away to study at the Russellville (Arkansas) School of Agriculture and Mechanical Arts, Sody got a job as clerk in Fietz’s Store at Gordon’s Gap.

Four years later when Noah came home with a secondhand army locker full of books, a sheepskin diploma and debts totaling somewhere near seven hundred dollars, Stinky Fietz fired Sody for being too lax with the credit.

Noah took over the family homestead, planning to upbuild it by means of Modern Agriculture and Inventive Mechanical Arts.

Sody undertook to sell lightning rods for the Protection of Homes and Loved Ones. In the course of seven months he disposed of one set to the countryside Bible scholar who meant well but was not able to pay; the Bible scholar was this writer’s maternal grandfather.

Brother Noah, meanwhile, planted 40 acres of bud-grafted apple trees and lost four-fifths of them in the course of a merciless and typical Ozarks drought which set in the following year.

Returned to his hilly homeland, Brother Sody took to peddling the Watkins Line of Helpful Household Handies. As he should have remembered, the backhill farm wives were usually lacking money and always limited in cash on hand. They were accustomed to washing their clothes in creek water, to making their own soap out of waste pork fat and lye leakings from wood ashes, and to seasoning their cookery with salt if at all.

Like many before and after him, Sody Porterfield quickly proved that backhill peddling does not pay.

Brother Noah had gone far toward proving the same as regards backhill agriculture. But Noah Porterfield was a man of hope — and meritorious reading habits. The latter brought him in touch with two publications of the University of Arkansas; bulletins entitled respectively “Profit from Peaches” and “Profits from Strawberries.”

Noah recognized both bulletins as being approximately one fourth literate and one-half hopeful; by unchallenged Mathematical Truth that estimate made the two together somewhere near half literate and wholly hopeful.

Accordingly, Noah replanted the drought-ruined apple orchard with peach trees establishing strawberries between the tree rows.

Sody, in turn, tried selling Granite State Monuments, again without success.

But Noah stayed with Scientific Agriculture for another decade. During the sixth year the peach trees, which had survived almost miraculously a succession of two utterly ruthless droughts, yielded a crop large enough to almost pay for the required sprayings.

For three successive years, the strawberries produced an average net loss of only a trifle more than a half a dollar a crate.

The peach crop was frost-killed three years in succession, but during the orchard’s tenth year the trees bore an enormous harvest.

So did practically every other peach orchard in at least 40 other states.

Markets collapsed, commission brokers absconded, and approximately six thousand bushels of Noah's peaches produced a net loss of nearly fifteen hundred dollars.

Immediately thereafter the trees ceased bearing and began dying.

With money borrowed at 10 percent at the county-seat bank, Noah changed over to Modern Dairy Practices which, besides being an almost overwhelming work load, yielded during the first year a net loss of slightly more than 40 dollars for each of the 11 Registered Jerseys.

A year later, Noah succeeded in selling all of the cows for a mere six-hundred-dollars loss and used the money recovered for making a down payment on a John Deere tractor with Minimum Accessories.

So equipped, he took a brief fling at mechanized hay farming. The tractor almost paid for itself in two years at which time it collapsed along with the rest of the enterprise in hay farming.

Meanwhile, Brother Sody had opened a country store, and as he presently confided, “Somehow sort of came in to meet himself going out to take the bankruptcy law.”

On a long, hot July night in 1920, the two brothers fell to comparing experiences and philosophies.

Both were showing gray about the temples; both had worked out their best years; both were weary and debt ridden.

So, as they rounded 50, the Porterfield boys became partners in moonshining.

Thereafter, they began to prosper modestly by making and selling usually drinkable moonshine whisky to fairly responsible customers. Neither was a stupid man. But both passed the half-century mark before perceiving that for the backhill economy, illegality is sometimes indispensable.

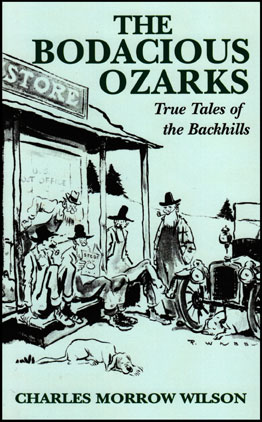

Pages 55-57, The Bodacious Ozarks: True Tales of the Backhills, Pelican Publishing Company, 1959

plate 1. Ozark Mountain High Road. Photo credit, J. Heston. May 5, 2008.

plate 2. Cover artwork on the Bodacious Ozarks by Paul Webb.

From the editor:

Charles Morrow Wilson — big-time journalist during the Roaring ’20s — possessed an edge in the dog-eat-dog world of journalism:

He was from the Ozarks.

His expertly crafted True Tales of the Backhills meanders artfully through the Ozarks with a careful humor tied inextricably to an equal dose of respect. His style closely resembles that of Harper Lee (author of To Kill A Mockingbird).

His comments regarding H.L. Mencken, the "redoubtable Sage of Baltimore," are worth the book price alone.

Ozarks culture? It's not an oxymoron and Wilson does well to bring this truth to light.

As editor of StateoftheOzarks, I highly recommend this book, first published in 1959 and now published by Pelican Publishing of Gretna, Louisiana.