plate 1.

Wooley Creek School

by Joshua Heston

A crisp, warm October afternoon. A bright autumn sun. Oak leaves rustling in the wind, framing the American flag, flying over a small, stone school house, high atop a ridge in the western White River Hills.

Folks gathered on this ridge decades ago and — thanks to the hard work of the Wooley Creek community — folks are gathering here again.

In the schoolyard, where generations of children played during recess, bluegrass musicians walk toward a stage.

plate 2.

plate 3. The Mississippi Sawyers perform.

Funnel cakes fry. Brightly colored lawn chairs seemingly sprout from the ground beneath the old oaks. Inside, a stream of curious festival-goers and former students wind their way between the old desks and around the potbelly stove, taking photos, reading the plaques on the wall, leafing through old photos, remembering (Plate 6).

plate 4.

plate 5.

plate 6.

It is the fall bluegrass festival out at Wooley Creek School, a one-room stone school west of Cape Fair, Missouri.

Members of the Wooley Creek community — including Doyle Branstetter, Oliver Foster, Janice Branstetter, Cindy Stull, Mariann Bruckner, Mike Collins, Glenda Chamberlin and Larry Sifford — have worked hard for six years, creating something of a revival for the small building full of memories.

It began on May 21, 2005. Floors were scrubbed with linseed oil and turpentine. Broken glass and litter picked up. Desks cleaned and arranged. The old place slowly came alive (Plate 5).

Wooley Creek School had been empty a long time. Consolidation took away the classes back in 1952 when students were assimilated into the Reeds Spring Reorganized School District No. 4.

A year later — August 12, 1953 — the property was signed back to the Wooley Creek School Trustees and their successors.

For 52 years, the school sat empty.

plate 7.

Named for the creek just down the rock road, Wooley Creek School overlooks the James River just as it widens to become Table Rock Lake.

This is West 76 country, a part of Stone County largely untouched by the bustle of Branson tourism or the proliferation of “lake people” both appreciated and derided by native Ozarkers (Plate 4).

It is not really known when the school was built, though the parcel of land was deeded over by Anthony Myers in 1903. There’s a good chance school was being taught here before then, likely in the building that stands today.

Originally a wood-frame building, Wooley Creek was stoned — by brothers Clyde and Claude Jones — with native rock between 1948 and 1951. The distinct giraffe stone is still in surprisingly good shape.

In addition to preserving the building itself, restoration committee members have been hard at work collecting stories of former students.

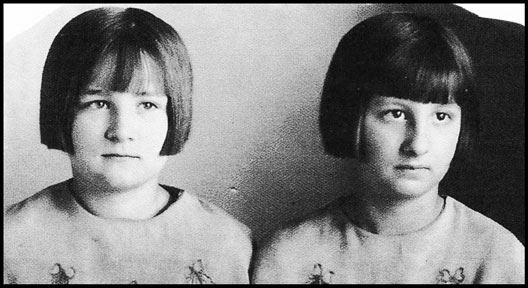

plate 7. Sisters Vera and Vada Stone.

Vada (Stone) Wilson remembers drinking water drawn from the nearby well, “There was no sanitation to it. We all drank from the same dipper but seems we never did get sick. I don’t remember us having colds. We were healthier than kids today. All the food was homegrown and not full of preservatives like today.”

Pie suppers, kangaroo courts, singings and church gatherings and Christmas programs were all part of the school’s yearly events.

“The kids would put on little short plays and programs before the pie supper. When someone bought your pie, it meant you would share a piece together,” shares Vada.

“We always had a Christmas program for our parents. It taught you to memorize and get a little fear out of you reciting in front of people. We would sing songs and have little plays all planned by the teacher.

“I remember one play when Clemma Foster played the part of the ‘mother’ and I was her ‘baby.’ I called her mama. Every time she would see me after that she would call me her baby.”

Wooley Creek was the center of the community.

Vada’s sister Vera would later teach a year at the school.

Glenda Chamberlin recorded her memories:

“Vera would ring the big bell on top of the school and the day would begin. Each morning would begin with roll call the pledge of allegiance to the flag and often a Bible verse.

“Reading classes were the first studies for the day, starting with the younger children. Older students were given assignments to work on silently [until the younger children were finished].

“Studies consisted of reading, writing, and arithmetic in the morning and spelling, history and geography in the afternoon. Arithmetic often consisted of “ciphering’ (working problems on the blackboard). Older students were allowed to help younger students.

“Ciphering contests and spelling bees would take place on alternate Friday afternoons. School generally dismissed at four in the afternoon but sometimes let out earlier on Fridays.”

Stories from the school continue to be gathered. The hard work of the Wooley Creek community continues to move forward.

- To restore and preserve Wooley Creek School, making it clean and safe, so it can once again be used by the community.

- List the Wooley Creek School on the National Register of Historic Places.

- Use Wooley Creek School as a living history center so that future generations can learn its history.

Their goals are simple:

Thanks to the hard work of a a group of dedicated, hardworking Ozarkers, the old Wooley Creek School is in good hands.

February 27, 2011