A Thoughtful Drive

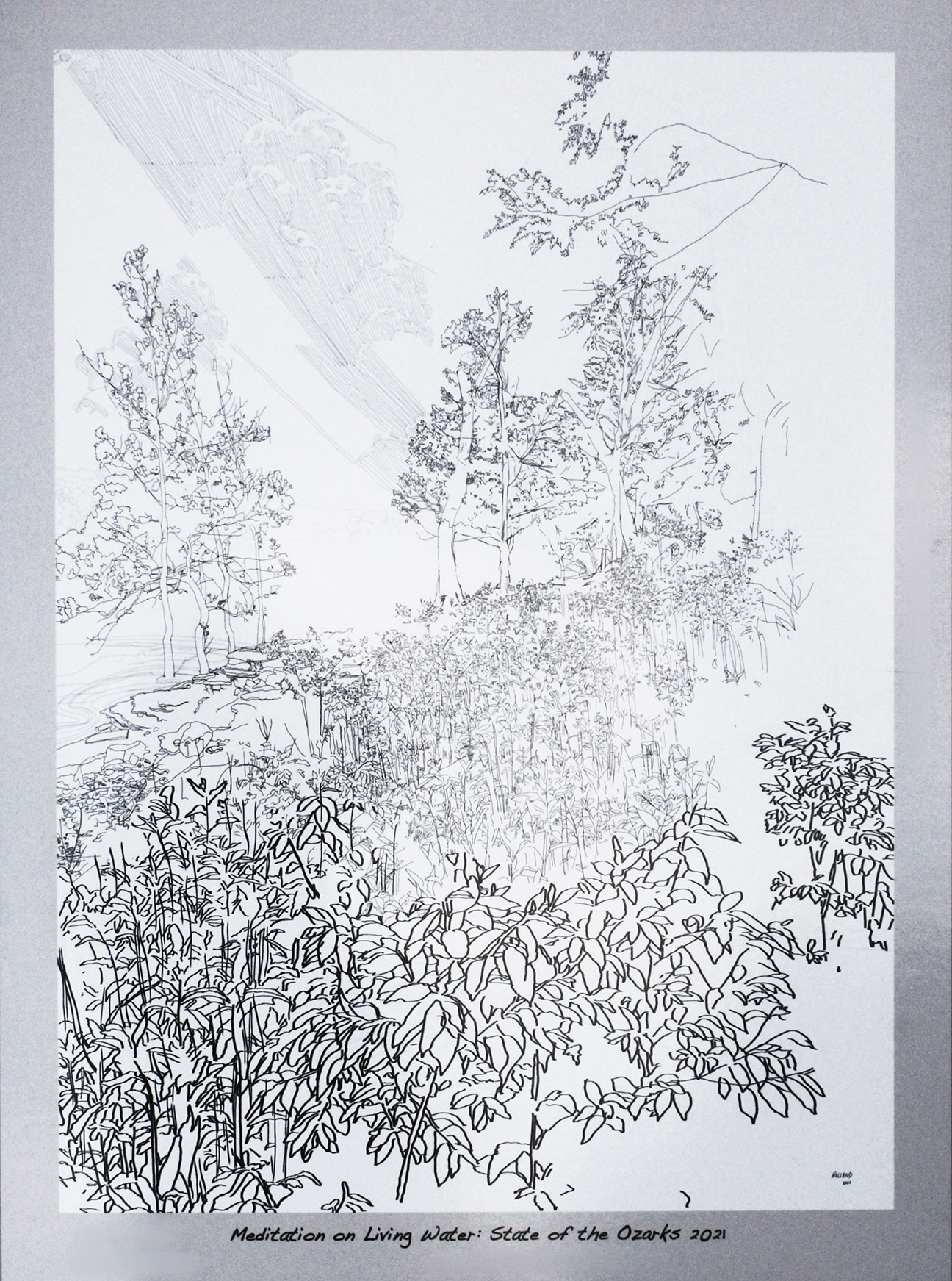

by Cindy Thomas with artwork by Brent Holland

Writers Artists Night 2021

Leaving U.S. Highway 65 at Leslie, Arkansas, Highway 66 meanders through the Ozark hills toward Mountain View. It winds past communities whose dominant—or only—feature is a gas station or tiny post office, alongside the occasional country church. Gently sloping from the north side of the highway, just before the post office of the same name, is Alco Cemetery. It has been there as long as I can remember. Judging from gravestones marked “Arkansas Infantry, Confederate States of America,” it was there long before that.

My earliest memories of Alco Cemetery are from the back of a pickup truck, or squeezed into the cab with Daddy if it was raining. We lived in a little white house down the dirt road north of the cemetery, and several aunts and uncles, plus both grandpas, lived somewhere near Highway 66 or in Leslie, so we went back and forth a lot. As we passed the cemetery, grown-up conversation turned to names like Clark, Richardson, Martin, or George, depending on which relative had most recently been laid to rest.

I never knew Grandma Hazel Martin Richardson, but I could walk right to her grave. She died in her late twenties, her youngest child just two years old, the grave marked by a roughly lettered stone. Great-uncles and older cousins rested under government-issued headstones from WWI and WWII. Aunt Lorene’s little baby boy had only lived one day. Mama seemed sad, talking about them, but she said we’d all be together in heaven.

Mama was closer to that point than I knew. Daddy had left his job in a Kansas airplane factory to return to the little farm near family because Mama was sick, and on July 12, 1961, Mama passed away, one month after my fourth birthday. A few days later, I stood at the east end of the cemetery with Daddy, Sis, and the relatives, wearing my best pink dress while our Assembly of God pastor from Kansas spoke the funeral sermon.

Ozarks tradition designated a special Saturday clean-up for cemeteries, followed by Sunday decoration and dinner on the grounds. Each little neighborhood cemetery had its day, reserving Memorial Day for those who died serving their country. Preachers from surrounding country churches took turns giving the sermon. Alco Cemetery’s decoration was the second Sunday in July, a few days before Mama died. Now big bunches of flowers on the fresh dirt of Mama’s grave, including her favorite pink roses, joined fresh flowers other families had brought to honor their departed.

We spent the next months in our little house, stopping regularly to visit Mama’s grave. Sis cried, but Daddy just stood with his hands on our shoulders for a few minutes before saying we needed to get home and do the chores.

That fall, a preacher named Brother Campbell decided rural Stone County needed an Assembly of God church. To jump-start things, he pitched a tent near the gravel parking lot of Alco Cemetery, not far from the highway, and held a week of revival meetings.

Since Mama had liked Assembly of God churches, Daddy was interested, so we went to the revival every night. One night it was raining. The sides of the tent were rolled up, and rain ran down the pitched tent roof, collecting in the rolls. During the long, loud sermon, I watched as one of those rolls became fatter and fatter, like a sausage.

Finally, the sermon ended. Somebody started playing the accordion, and Daddy went forward to pray at the wooden altar bench. He told me to sit still and wait, but the temptation was too much for a bored four-year-old. Spying a stick nearby, I slipped over and got it and poked that nice fat roll of canvas. The sausage collapsed; water shifted and poured down right on some people standing near the tent pole. A man jumped and yelled, and a lady screamed as the cold fall rain gushed down her dress. I, of course, dropped the stick and hid behind a suitcase full of hymnbooks. I guess the people up front thought the Holy Spirit had fallen in the back, because they kept right on praying. And I realized there must be a God in heaven who cared about me, because nobody saw who had caused the trouble, and Daddy never found out.

The church moved into a new concrete block building, and there weren’t any more tent revivals that I recall, but to this day I smile as I drive by the spot where that tent was pitched. I laugh out loud if it happens to be raining.

Over the years, the cemetery gathered more special reminders. Grandpa Richardson died, and the family chipped in for a new double headstone and moved Grandma Hazel’s old one to the foot. Daddy married Mama’s youngest sister, who had lost a fiancé in WWII, and we moved back to Kansas and his factory job, but I was always glad when Daddy’s vacation coincided with Decoration Day. I liked to wander among the stones thinking about relatives I had barely known or only heard about. The oak tree where we gathered for the sermon and dinner grew huge and spreading, moss growing on the rough benches underneath.

Two of Mama’s sisters joined her in the east end of the cemetery. An eighteen-year-old cousin’s grave became a tragic reminder to take having a driver’s license seriously. Another cousin left us far too soon, my first awareness of clinical depression.

As the years slip by, Decoration Day has become sparsely attended, and we hire out the mowing instead of gathering to do it. The memories of the older graves have grown distant, fading like the flowers, crowded out by busyness as weeds choke the morning glories along the fence rows. Around Memorial Day, new flowers show up on more recent graves; we have good intentions but also jobs and health challenges of our own.

So, we go on, chatting occasionally on social media and making our contributions to the cemetery maintenance fund. Thanks to modern technology and a cousin who tackled cleaning and photographing some of the oldest gravestones, one can browse historical websites if curious about a name or date.

But inevitably, we gather for another funeral and Alco Cemetery once again brings us together. My stepmother joined her sisters in the family plot, leaving space for Daddy between her and Mama. Daddy, the last living uncle on both sides, is too frail to attend. Standing among our dwindling number, we talk of planning a get-together before another funeral does it for us. We share pictures of kids and grandkids who couldn’t make it to the service. As the grave is closed, we wander off to reminisce once more over the inscriptions on the surrounding stones.

Occasionally I travel that way to see a cousin. I always slow down, or actually stop if I possibly can, because Alco Cemetery is the perfect pause to reflect. I think about the folks waiting for me in heaven, and I resolve to do the best I can with whatever time I have left.