Castle Ghosts: Pythian Castle

by Joshua Heston with Stephen Meek

There was a knock on the heavy oak door, a door sheltered beneath massive Carthage limestone. “So, have you met the ghosts?” The question came from a covey of OACAC non-profit agency employees, former daytime residents of the Pythian Castle — a monolithic structure of Gothic towers and subterranean passageways now practically sharing space with the Evangel campus in the northern reaches of Springfield, Missouri.

“Well, maybe,” replied Tamara Finocchiaro, a bit taken aback. Finocchiaro, the castle’s newest owner, had taken on responsibility of this historic building after learning it was in danger of being leveled to make yet another parking lot. She would later recall that yes, she had met the ghosts. “We had paint drapes covering the doorway of the writing room,” an expansive chamber in the west wing of the castle. “When I walked back into the hallway, I pushed through the drapes and encountered a physical body standing on the other side. I bumped into it!” Finocchiaro was alone in the castle that day.

That was only the beginning. Yes, there had been the whistling melody in the foyer, the droning murmurs of a crowd in an empty room, then the footsteps throughout the place. Finocchiaro had spent an hour checking all the window locks that day, looking for a trespasser.

The renovated castle was re-opened to the public in 2010 as a venue for weddings, proms and other parties and now regularly schedules history tours, murder mystery dinners and late-night ghost tours. The Discovery Channel’s Ghost Lab featured the Castle in 2011.

The ghost tours are particularly popular come October. “The phases of the moon change the frequency of the ghost sightings,” sighed Cindy, our ghost tour guide for the evening, “and Halloween is an especially good time for ghosts.” Willowy and animated, Cindy did not disappoint as she led her cadre through the Castle’s professed hauntings and deeper into the building’s extraordinary history.

The Knights of Pythias — a fraternal organization dedicated to loyalty, honor and friendship — had the Castle built in 1913. In those days, the work of the Knights was highly respected. Springfield outbid Kansas City and St. Louis for this Pythian Castle and promised a trolley line to downtown (a not-inconsiderable distance in those days), the renaming of the street (now East Pythian Street, just off Glenstone), the construction of a nearby school, and the purchase of the 400+acre property, awarding the property to the Knights for only one dollar.

The Castle served dual roles for the order: a genteel rest home for aging knights’ widows and an orphanage for knights’ children. In the days before social workers and government-funded welfare, a major benefit of the fraternal order was a sense of security for loved ones.

It could be an imperfect solution. The orphanage was open only to children of a knight. One mother brought her three children to the Castle to learn only two would be allowed. Her third child’s father had not been a knight and therefore was turned away, the family divided.

In the impressive foyer, matching staircases rise to the second floor. One for boys. One for girls. During the children’s stay at the Castle, boys and girls were kept separate at all times. One boy ran away when the loneliness simply got too much. His caretakers wouldn’t allow him to see his younger sisters, separated only by walls.

“I was standing in this corner when a child’s voice said, ‘Hello!’” notes Cindy as we step into the east wing of what was once the children’s second-floor dormitory. I said, ‘Hello’ right back and looked around. There were no children anywhere to be seen.” Cindy’s festive headpiece of felt bats bobbed most impressively as she shared the experience. “That’s when I knew I wanted to work here. I don’t like being scared but this place baffles me. I don’t watch horror movies, but there’s something compelling, something that draws me here.” Almost by magic.

Currently, the castle’s magic is augmented by a number of devices, all scorned by traditional science. Throughout the tour, Cindy’s “ghost app,” a smartphone application said to “detect paranormal activity,” beeped, tweeted, whistled and occasionally spouted random words. An EVP (electronic voice phenomenon) recording captured in the castle seems to whisper the word Lillian, played to considerable effect during a tour of the theater room.

Some paranormal experts believe ghost activity is concentrated where there were once many intense emotions, particularly at the time of death. A good portion of the “science” is simply historic research to uncover what happened within a certain space. But perhaps the ghosts are here for more primeval reasons. The heavy Carthage limestone from which the castle is built is said to focus — and possibly entrap — spirit energy.

However, we scarcely need mystic limestone for the memories trapped in this place. There were children who spent their entire childhoods here. What would that have felt like? We know they worked hard. There were cows to be milked, weeds to be picked. The gardens and livestock mean the location was also a farm and largely self-sufficient. No Sysco food truck for these kids but rather pails of steaming milk on the frigid winter mornings. There would be black snakes curled up under the strawberries, yellowjackets in the trees, and the first of the spring radishes, the last of the summer tomatoes. Many children would grow up to remember their years here fondly.

And yet, those moments, thousands of them, were contrasted with the elderly living here simultaneously, musing, recollecting, reflecting on their lives. Had their lives been lived fully? Did they feel satisfied with the conclusion? For that is what they were here for — their conclusion. Put out to pasture, waiting to die. All our lives are spent creating a sense of meaning and hope. But their arrival, no matter how beatific the organization, was unmistakable. Their races were to conclude here, possibly far away from their children or grandchildren.

How different did those elderly lives end, here in a castle near now-downtown Springfield, from their hillbilly counterparts only a few miles away in the hills? Those poor hillfolk, often surrounded by the younger generations they had sired, may have weathered away on a rough rope bed. Perhaps the hounds bayed when the moment of death arrived. There is a strange juxtaposition here — remnants of a formal, Edwardian age replete with gentility coexisting with a nearby near-Elizabethan culture, of mountain life not-far removed from Appalachia or the dirt-poor of the Celtic Isles.

But regardless, those elderly in this old building died here. Were their passings peaceful? Hopeful? Sad? Angry? With 80 documented deaths in the Pythian Castle, that’s a wide gamut of emotion. Regardless of what anyone believes about ghosts, this is high drama within the walls of one of the most evocative structures in Springfield, if not all the Missouri Ozarks.

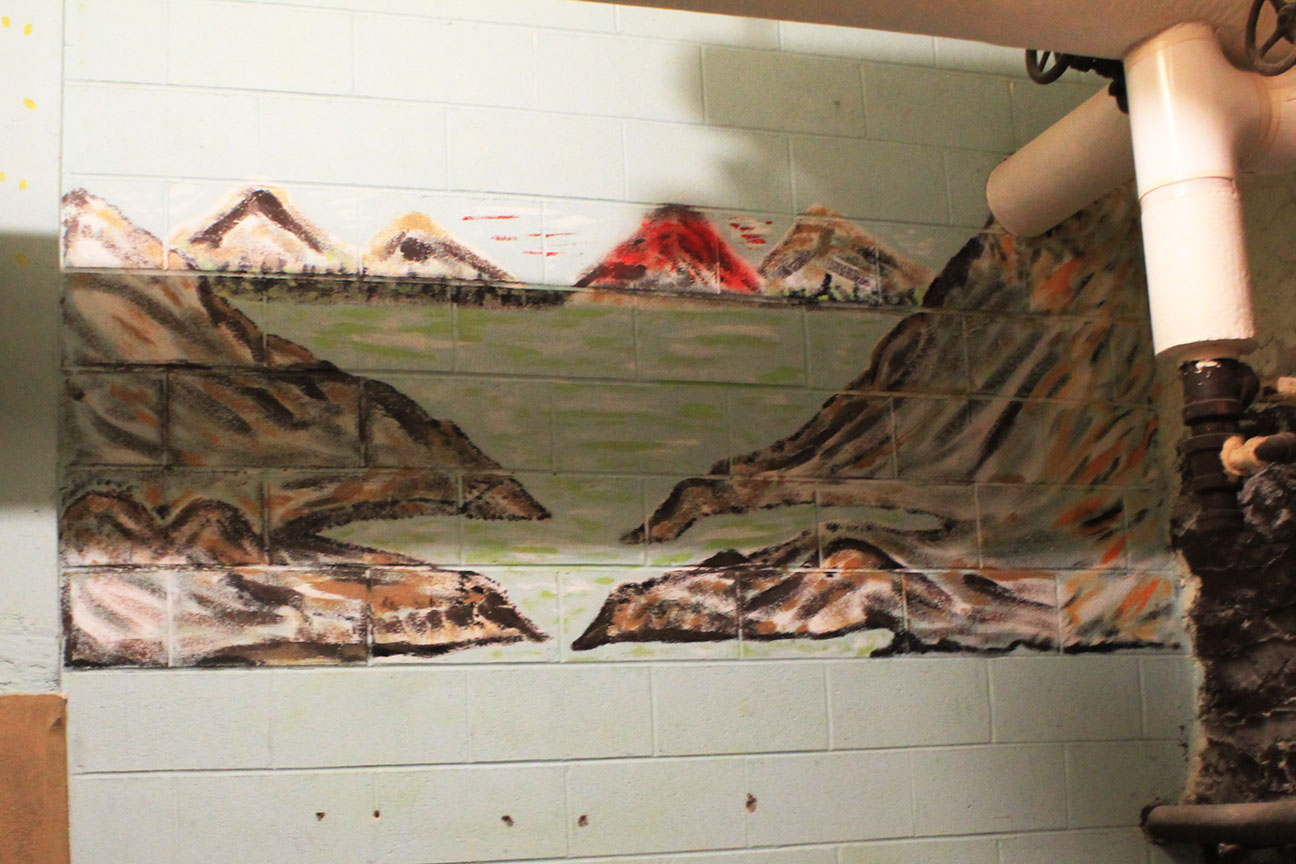

In 1942, the Castle’s story would change dramatically. The US government expropriated the building, converting the farm into a troop camp of sorts, mainly for injured servicemen. There was an army hospital here as well and — to further the place’s drama — captured German, Italian and Japanese soldiers were kept as prisoners. “The high ranking Germans treated the nurses very badly,” shared Cindy as we worked our way through the basement prison cells. “They screamed at the nurses, spat at them. The Japanese soldier, however, was well regarded and treated those around him with great respect.” So much so, he was allowed paints and paintbrushes, resulting in a gentle mural of mountain and sea on his cinder block cell wall.

Viewing the artwork can be unsettling. This man, so far from home, a prisoner in an alien land, whiling away his time in a tiny cell, waiting to return to a place he would find irrevocably changed. The peaceful realm he painted on this cinder block Missouri wall was thought an impregnable and sacred island stronghold — the one place on earth no enemy could touch. This reflective solder would return from his Ozarks imprisonment to find his cities burned to the ground, irradiated, devastated, leveled with bombs both nuclear and incendiary. Who was this man? What became of him?

This was the same basement wherein a neighbor boy during the ’60s would sneak in to play with his “friends.” “I would break in all the time,’ he remembered. “It was great fun.” When reminded the Pythian Castle was deserted during that time and certainly no children were there, he recalled, “That’s funny. They moved my toys around on the floor like real kids!” Children’s toys have been found in the walls down here.

Upstairs, however, the scene during the war years was more convivial, though perhaps no less reflective. In good farmboy fashion — for that is what most of our troops were in those days — the square columns of the formal dining room were roped off… for a boxing ring! Dances were held here regularly, as the prettiest and most eligible of Springfield’s young women arrived to flirt with handsome and willing soldiers. Bob Hope even entertained here, upstairs, in the theater which also served as a church sanctuary. “They held funerals here,” said Cindy, her felt bats continuing to bob cheerily as she pressed play on the EVP recording that whispered one word: Lillian. “We don’t know who Lillian is yet.” But the skeleton band on the stage was churning out Freddie Mercury’s Another One Bites the Dust as we filed out.

“It’s an orb!” breathed the woman next to me, waving her iPhone in front of her, tracking strange light artifacts through the room. Orbs are “balls of light found in photos of allegedly haunted places,” according to TheShadowLands.net. Cindy called them “light caused by spirit energy flowing through the air.” In the east wing of the second floor, the light sources were many, casting weird shadows in all direction. “There’s another one! At my feet!” exclaimed the woman. This crowd of Springfield couples — looking for a little excitement on an otherwise boring Friday night — were beginning to think their smartphones were showing more than they may have bargained for.

Such experiences lead to reflection. Who were these people, out for a little Friday night fun? Average couples, professionals, perhaps “hanging on in lives of quiet desperation,” as intoned by Pink Floyd. We are a people living socially prescribed lives, often feeling disconnected from the enchanted, the magical and, quite possibly, the hopeful. We want to touch the “other,” and chill with delight. But when the tour began and actual ghost experiences were described, the crowd’s mood began to shift. Perhaps this is real? Yes, there was a desire to touch magic, enchantment, a welcome change from the cubical, the mortgage, and the unruly teenager. But there was also a sudden ripple of fear that this magic might — just might — be real.

Almost in relief, the payoff came in grainy iPhone light artifacts which gave an intellectual sense of “something more” but did nothing to enlighten or ultimately remove us cursory ghost hunters from our de-sacrelized world. But that is not surprising. Rarely are mortals allowed to view upon the otherworld, not because the otherworld isn’t there but because we really are too irrevocably harnessed to our cubicals, our mortgages and our unruly teenagers. It would permanently unhinge us to find that for which we seek.

But there is a melancholy irony in ghost hunting. If one compares the limitless aeons of time with our own spare moments on earth, it is not the supernatural that is largely absent from the great history but rather our own fleeting — should we say ghostly? — traipse through mortality.

— originally published October 28, 2015