Red Oak II

by Joshua Heston

[JASPER COUNTY, MISSOURI] — A sharp wind whistles across the rolling Missouri plains east of Carthage. Here, less than a mile north of famed Route 66, is Red Oak II, a community that isn’t a town, but a tourist attraction that is a homey neighborhood of museum-esque eccentricity. The place is easy enough to find. Just turn north on County Road 120 after you see the “Crap Duster” at the Flying W Truck Stop (if you’re traveling west-to-east on the Mother Road).

If you’re traveling east-to-west, you ought to turn around at the “Crap Duster,” but not before studying the green barnstormer towering firmly over the shrubbery. The body of the plane is clearly an old-fashioned manure spreader.

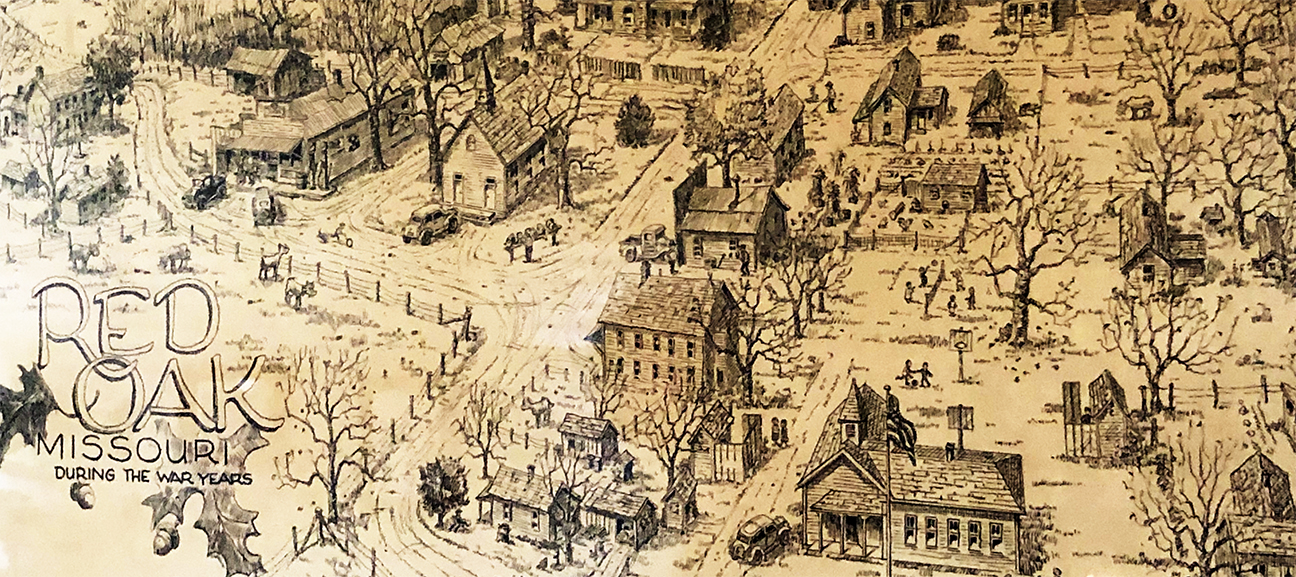

The first Red Oak was not far away as the crow flies, north of Plew and east of Avilla. Today, that town is gone, a victim of post-war industrialization and for having the misfortune of being platted just a little too far north of Route 66.

Red Oak II exists because one of Red Oak’s sons, Lowell Davis, would all-but recreate his hometown in a cow pasture, a monument to nostalgia — and something more besides.

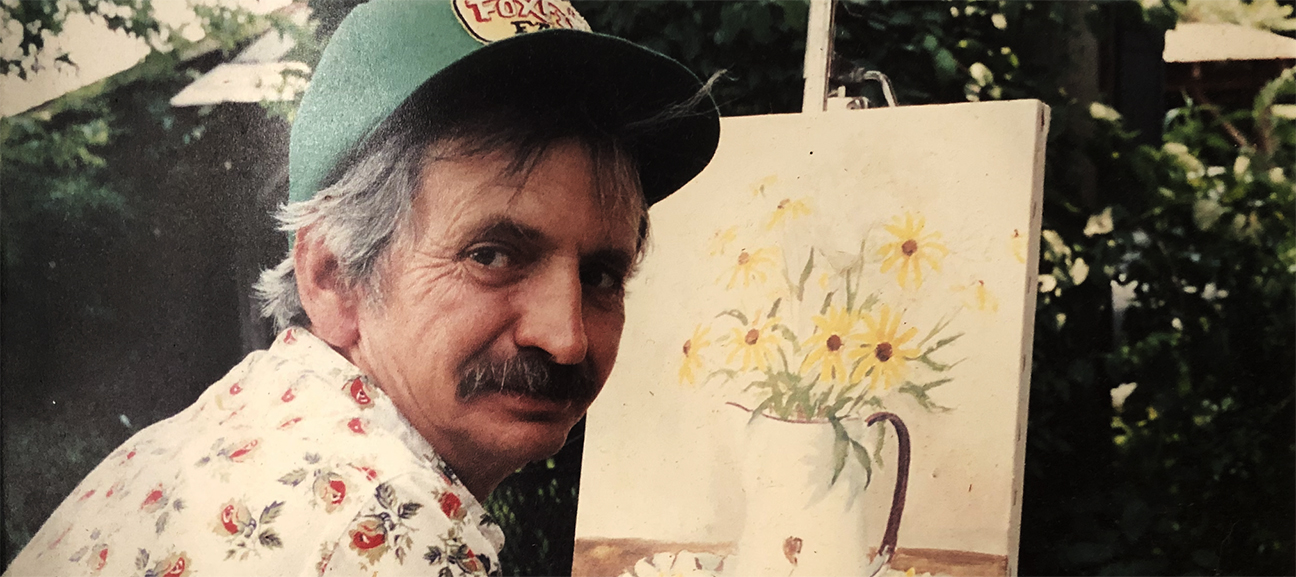

Davis was born in 1937, flunked his high school art class, and joined the Air Force where he served with pride until an Algerian landing mishap sent him through an instrument panel. He would return, not to Missouri, but to Dallas, Texas, working for an advertising firm and finding time to provide art direction for Sex to Sexty, an American novelty magazine dedicated to all things bawdy, albeit under the pen name Pierre Davis.

But Davis hated the big city of Dallas. He returned to Missouri, remaking himself as the “Norman Rockwell of Rural Art,” and merchandising figurines, paintings, prints, bronzes, and storybooks. The inspiration? His “Foxfire Farm,” where he began moving the remaining buildings of Red Oak, replanting the blacksmith shop, general store, and schoolmarm house to the low-lying and often-swampy farm ground.

Much like the pick-pocket crows he immortalized in a Red Oak II sculpture, Davis began procuring stranger and more unique buildings. The farm became subdivided, with many properties becoming others’ private residences, while at the same time, Red Oak II became a notable Route 66 destination.

Red Oak II resident, parson, farmer and part-time showman, Jeremy Morris, lives “midtown” in the Parsonage “II.” The home may have once been a brothel. Morris often gives visitors impromptu tours of the acreage. Catty-corned from the Parsonage is the Dalton House, childhood home to the boys who grew up to be infamous outlaws, moved here from Vinita, Oklahoma. Out back of the house, an amusement park train gathers dust in the barn and a jalopy is parked next to the windmill.

The log cabin next to the Dalton’s is the newest to Red Oak II, and the oldest building in this “open-air museum.” It is the log cabin of George Hornback and the first courthouse of Jasper County, Missouri. Had the cabin not been moved here, it would have been torn down.

“We call this the Civil War House,” says Morris, gesturing to the white farmhouse with black shutters. “It was originally built near [where] the White Oak Massacre [took place]. We call it our Amityville House.” Flickering lights have been seen. Strange noises heard. “If anything is haunted, it’s that one.”

Across “town” a rickety Lockheed Electra 120 stands poised as though ready for flight, even as it is missing an engine. Red Oak II is a strange monument to quirky Americana, often exactly that for which Mother Road tourists clamor.

“The international tourists spend, like, a month, touring Route 66. They do it slow. They may live next to the Coliseum but they’re excited by a real American chicken egg.

“You learn to adapt, go with the quirkiness, lean into it, don’t fight it.”

Once Morris jumped at the chance to “hop into an old ’51 Cessna” for aerial photographs of Red Oak II. It was Saturday evening. The pilot buzzed the town so low the church’s jam session musicians ran outside as the building’s windows shook. Such an incident seems more expected here, somehow encapsulating the American sense of an irrelevance for conformity.

Red Oak II has two gas stations. The more easily overlooked Standard Oil may be the oldest on all of Route 66. “It was a kit. Somebody got home from World War I and needed a business.”

Three women in their early 20s are busily photographing themselves in front of the nostalgic gas pumps. “Something happened after 2020. Young people are into Route 66 now.”

A “Prairie-style” house stands in ocean-front colors, notable for its exterior stairs to the second floor. “That usually means a brothel,” notes historian and author Lisa Livingston Martin drily.

A centerpiece of Red Oak II is the green-sided Belle Starr home. Born in Jasper County as Myra Shirley, the “bandit queen of the west” nursed dying soldiers on the Carthage Square as the Union shelled her town. She was murdered at age 40 near Eufaula, Oklahoma.

“The cabin [portion] was added to make it a replica of the house where she died.” The green portion is the original Shirley farm house. Starr’s father was the largest landholder and slaveholder in Jasper County before the Civil War.

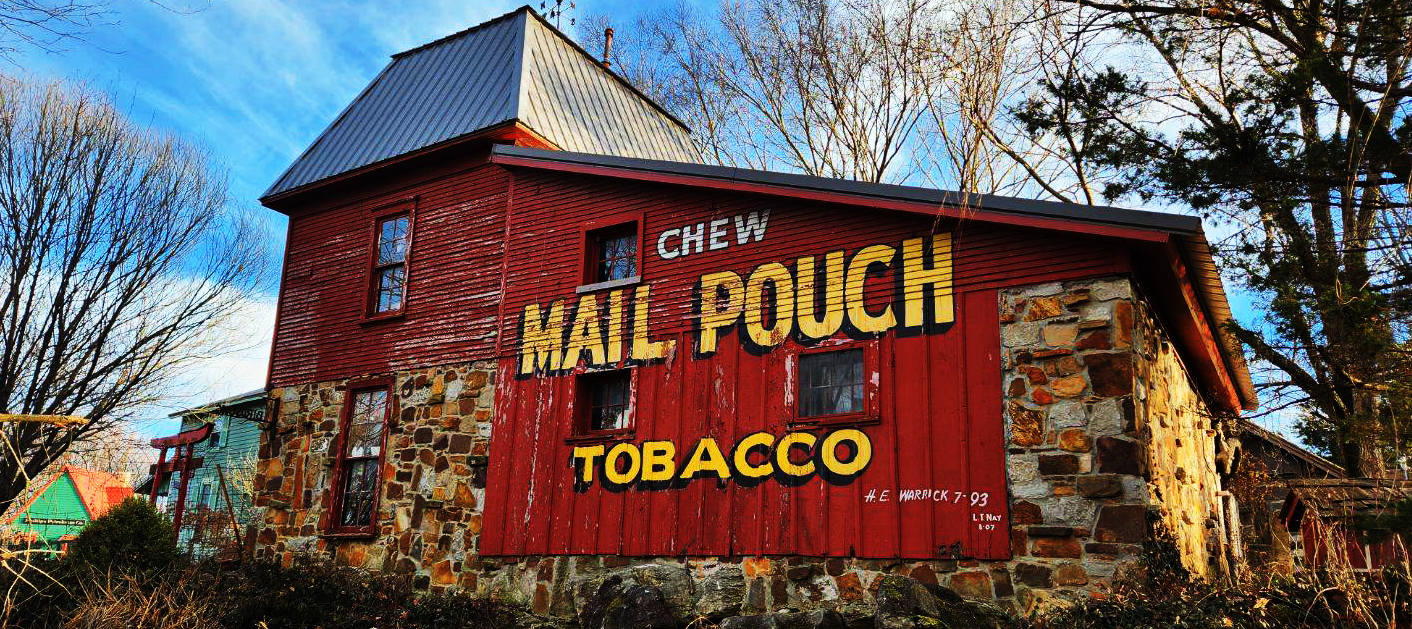

Today, Starr’s backyard is accessed by the Bird Song Gallery. Here the blue shell wind chimes rattle and a mannequin with an oddly familiar outline stares quizzically from behind a counter. The art gallery is in the mill-like barn upon which Harley Warrick painted one of his last “Mail Pouch Tobacco” signs in 1993.

“It’s literally an art piece,” exclaims Morris, gesturing to include the entire farm. “I’ve lived here five years and keep finding new stuff. There’s a man’s ashes buried in the fountain.”

At the south end of the “bayou” (actually one of two extensive frog ponds), something resembling a witch’s cottage rises precariously from the cattails. Inside, all is strange angles in green. The ladder to the loft was removed recently. “We found a couple up there, uh, trying to stay warm,” murmurs Morris.

Back up the gravel road, the fantasy turns decidedly western. The marshal’s office is a popular location for low budget filmmakers, the carefully planted yucca lilies standing in admirably for real desert cactus.

Next to the law office is another old-time cabin. “Lowell said that was a slave cabin but I don’t know.” Across the street is the jail, an imposing iron cage believed to be the turn-of-the-century drunk tank used for rowdy Joplin, Missouri miners and ne’er do’wells. From behind, a covey of peacocks call. Davis’ real-life farm was used as inspiration for his art.

Hidden between the Belle Starr house and the slave cabin is Morris’ favorite of Red Oak II’s 10 outhouses.

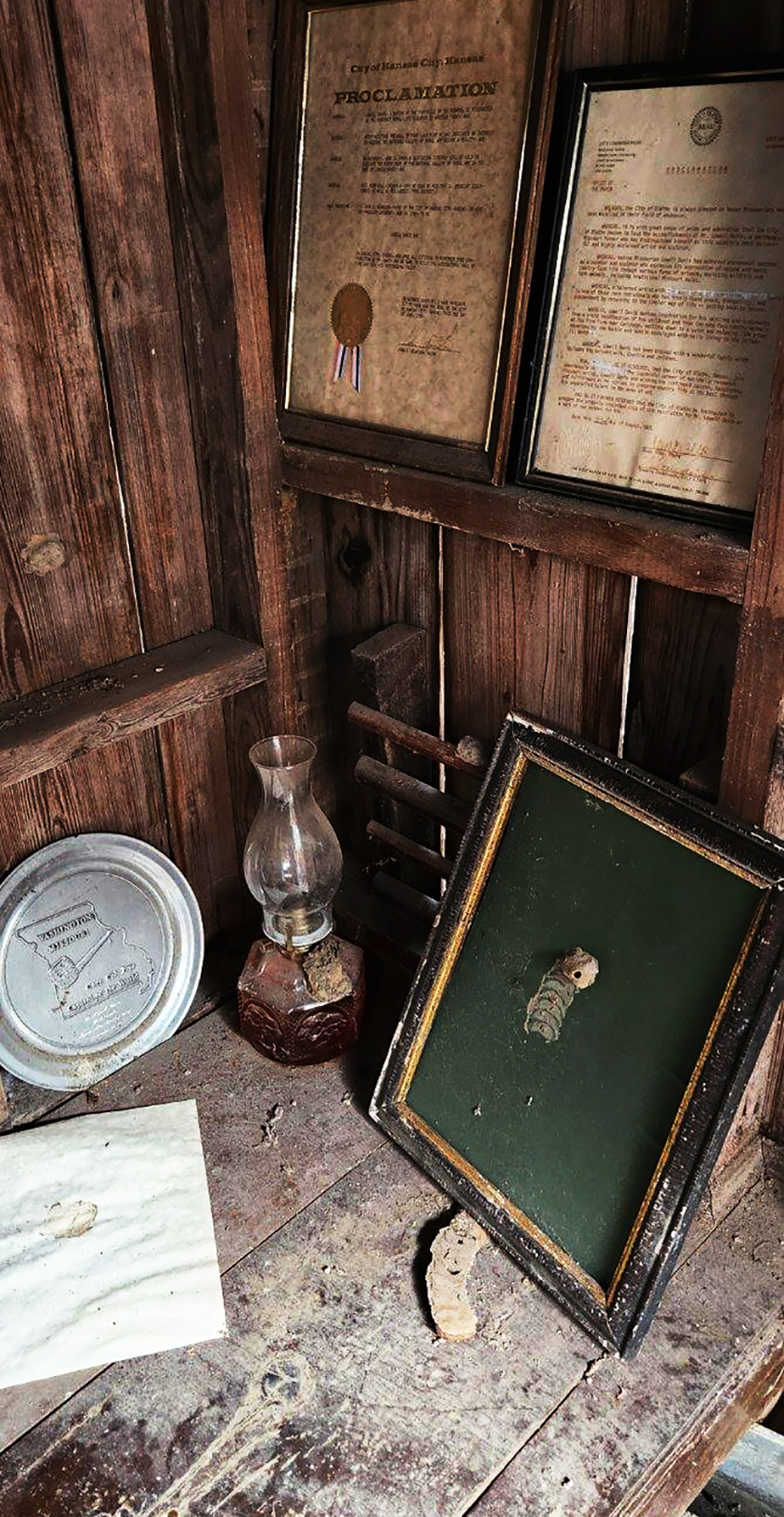

“When Lowell would get awards, all that stuff, this is where he would put them.” The outhouse is littered with various trophies and plaques.

“The only exception is the painting Andy Thomas gave him, painted in Lowell’s style.” Davis had mentored Thomas, now an internationally collected artist. When Davis received the painting, Morris recalls, “Lowell started crying and then said ‘If I’d have known Andy was gonna be a better artist than me, I would have broken his hands.’”

Scant yards beyond the outhouse, a green mound of graves rise.

“People ask if it’s a real cemetery,” explains Morris. “The people were real. They’re not buried here. When stones were replaced by monument companies, we got permission to use them.”

There is one exception. Surrounded by his art and on the farm he loved, the remains of Lowell Davis are interred. Davis passed in 2020.

“It’s just a place for the creative,” Davis said once. “Jeremy, keep it art. It don’t have to be my art. But keep it art.”

The sun sets on Red Oak II and the wind is still blowing. Last light of winter’s day flickers over Davis’ rendition of himself driving “Emery,” his beloved Ford pickup. Lowell Davis may have gone on but his dream is not yet dead.